Drug retinoids – tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene and trifarotene – are some of the most powerful ingredients in skincare. They can help with issues like acne, uneven texture and hyperpigmentation.

But what are the differences between them? Here’s the guide for you!

My PhD is in medicinal chemistry, so I’m going to be diving into the differences at a drug structure and formula level, as well as at a more macro “results” level.

The video version of this is here, keep scrolling for the written version…

Drug versus cosmetic retinoids

I talked about the differences between drug and cosmetic retinoids in this post – in short, drug retinoids are more regulated for efficacy (of the active, as well as off-the-shelf formulas), and there’s more of a guarantee of efficacy and stability. Cosmetic retinoids have greater flexibility in formulation (good for reducing irritation, and for availability). Compounded “custom” retinoid formulas are often presented as the perfect combination of effective drug and cosmetic flexibility, but actually lose a lot of the advantages of both.

This time we’re going to dive deeper into the the different drug retinoid actives.

Which retinoid is best for what?

The most common question I get asked about drug retinoids is which one works for what condition – for example, does adapalene do anything for anti-aging, or does it only work for acne? Is tretinoin the best all-rounder retinoid because it works at all of the retinoic acid receptors?

In my opinion, all of the drug retinoids generally work for everything. There’s stuff online about receptors and clinical trials saying one is better than the other (I’ll go into that in this article), but there are a lot more similarities than differences in how they work. The main differences mostly come down to practical considerations, like what other ingredients they’re formulated with, and what percentages are available.

Tretinoin

Let’s start with tretinoin, the oldest drug retinoid, which was approved in the 1960s. It’s been studied the most because it’s been around for so long – most of the evidence we have on retinoids are from tretinoin studies, and it’s been shown to work for all the standard retinoid things, including acne, pigment, and wrinkles. There’s a few studies on more random things too, like skin cancers, red stretch marks and cellulite.

Concentrations

Tretinoin is the drug retinoid with the most formulas available. It’s pretty widely found at concentrations between 0.025% and 0.1%. It’s also the most common one used for compounding so you can get other percentages reasonably easily too (although how that compares to off-the-shelf drugs is questionable – I talked about the issues with the efficacy of compounded formulas in my last post).

The studies so far suggest that the lower concentrations of tretinoin will end up giving similar effects, but with less irritation.

Formats

Tretinoin comes in both gels and creams. There are some studies that indicate that cream bases for retinoids are less irritating, but my personal theory is that this might just be because the creams essentially forced the people in the studies to use moisturiser (a lot of studies didn’t include moisturiser otherwise, and a lot of the study participants were males aged 12-25 with acne – not really a demographic known to use moisturiser). A lot of the irritation from retinoids seems to come from barrier disruption, as a result of retinoids just doing their job (increasing cell turnover, which means the cells in your skin barrier might not be maturing normally when you start using them).

There are also fancier versions:

- Altreno has a nicer lotion base and is less irritating

- Encapsulated versions like Retin-A Micro, which contains tretinoin in microspheres, are generally gentler since they release tretinoin more slowly

- Avita gel contains a polymer which works in a similar way

Combination formulas

Tretinoin also has the most combination formulas, which are convenient for targeting particular issues. For acne treatment, tretinoin is particularly useful because it breaks up clogged pores, so other ingredients can penetrate better. Some examples:

- Twyneo contains 0.1% tretinoin and 3% benzoyl peroxide, separately encapsulated in silica-based microcapsules – both are great treatments for acne, but benzoyl peroxide is a good oxidant, so it usually breaks tretinoin down

- 0.025% tretinoin can also be found with 1.2% clindamycin phosphate, an antibacterial for acne treatment

For fading hyperpigmentation, triple therapy creams target multiple causes at once. For example, Tri-Luma combinea 0.05% tretinoin with 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide (a corticosteroid which decreases inflammation) and 4% hydroquinone (gold standard pigment treatment).

Related post: Fact-check: The Dangers of Hydroquinone

Also, because tretinoin is older, there are more generic options of many of the above formulas available, which are usually cheaper.

Why newer retinoids?

Tretinoin is pretty solid, but there are a few downsides, which led to the development of newer retinoids.

Stability

Tretinoin is pretty unstable: it breaks down relatively quickly in light, in heat and with oxygen.

It isn’t so unstable that you’ll have to worry about turning off the lights or blocking off oxygen after you’ve applied it (though it’s probably a good idea not to go into direct sun immediately). The concern is more about how long it’ll last in its packaging – a lot of effort has been put into making stable tretinoin formulas.

Tretinoin also gets broken down by benzoyl peroxide. This is an issue since it’s the other main acne treatment, so using them at the same time runs the risk of inactivating the tretinoin (aside from in special combination formulas like Twyneo).

Irritation

Tretinoin is also pretty irritating. One of the main reasons people left clinical trials for tretinoin was because of irritation, and plenty of people give up on it before they see any benefits. There are lots of guides online about how to start on tretinoin, including from me.

Related post: How to Start on Tretinoin (Retin-A) and Retinol

As explained in my previous post on drug vs cosmetic retinoids, irritation is partly to do with how retinoids work, but it doesn’t seem to be necessary for the retinoid to work.

Related post: Drug, cosmetic or compounded retinoid: Which one should you use?

Receptors

There are ways to make tretinoin formulas more stable and less irritating, but there’s also potential to build these properties into the active ingredient itself.

Here’s where receptors come in. To work, retinoids need to bind to retinoid receptors (RARs) in the skin. It’s a bit like the retinoid is a key that fits into a lock (the receptor) to make something happen (the microscopic changes that eventually lead to skin benefits).

There are three different RAR subtypes that have slightly different binding pockets – essentially, they’re three locks with slightly different shapes.

- Gamma RARs are the main ones in skin, and are responsible for retinoid-related skin benefits

- Alpha RARs are also in skin, and are at a slightly higher level in the dermis than the epidermis

- Beta RARs don’t show up much in skin (although they do pop up after using retinoids), it’s generally thought they aren’t that involved in skin effects

Tretinoin binds to all three receptor subtypes (alpha, beta and gamma). In medicinal chemistry, this is generally something you don’t want. Most drugs have their beneficial effects mostly at one receptor type – when it hits the others, you usually get more unwanted side effects, and lower potency. The technical term for this is “promiscuous” – it’s almost like they’re trying to slut-shame the drug into behaving better.

(Unfortunately some people who don’t have actual expertise in this area have promoted the myth that an ingredient hitting more targets makes it “a beast”, when it’s a basic principle of drug design to aim for the opposite.)

So following this standard reasoning, drug companies started designing and testing ingredients that bound more to gamma and less to alpha – in theory, this could give the same benefits as tretinoin, but with less irritation. This led to adapalene and tazarotene:

Both have aromatic rings in their structures (the hexagons with alternating double and single bonds), which makes them more rigid, so they don’t fit in as many locks as floppy tretinoin. Both bind to gamma and beta RARs much more than alpha (technical term = more selective).

These rings also make them more stable to light and oxygen. As well as being more robust, this could also potentially make them less irritating, since tretinoin breaks down to produce some irritating substances.

(Note: these are called “3rd generation” retinoids because there were also 2nd generation retinoids made earlier with a single aromatic ring in their structures, but they aren’t used much for skincare.)

So did it work?

Well, adapalene does seem to be less irritating than tretinoin, both in clinical trials and anecdotally. So yay, science works!

But tazarotene is a different story. While early data found it to be as irritating as other retinoids, later studies have found that it’s more irritating, and pretty much every dermatologist who prescribes retinoids and every user who’s tried them will agree.

So, it doesn’t seem like there’s no straightforward relationship between RAR subtype selectivity and irritation. This makes sense, because it seems like a large part of retinoid irritation comes from how they work, so activating the gamma RARs inherently leads to a lot of the irritation.

From looking at all the evidence, I think irritation – and many other differences between retinoids, like effectiveness for different conditions – has more to do with other factors, such as:

- other substances in skin that the ingredient might bind to, and where they end up in the skin (e.g. based on their physical properties – this is called pharmacokinetics if you want to read up on it)

- what formulations and strengths you can get them in

(Interestingly, a 2023 manufacturer-funded study found that a newer 0.045% tazarotene lotion (Arazlo) was less irritating than 0.005% trifarotene and 0.3% adapalene, which would support this idea.)

Adapalene

Adapalene was approved in 1996 for treating acne:

The funky cube thing on the left is adamantane, and it makes the overall molecule more oil soluble. This helps it go into hair follicles more, where sebaceous glands are, making adapalene good for targeting acne. The particle size used in common formulations is also optimised to target hair follicles.

The adamantane also helps adapalene stay in the skin rather than absorbing deeper, into the rest of your body, which makes it safer.

This extra safety is why 0.1% adapalene gel is currently the only drug retinoid available over-the-counter in some countries (approved in 2016 in the US). The main concern was possible birth defects if someone used it while pregnant, but it was approved because:

- It’d been used on a prescription basis for 20 years without issues

- Tests were done to work out the margin of safety, which was large even with potential misuse

- The only other good over-the-counter acne treatment at the time was benzoyl peroxide

Concentrations and formats

The original 0.1% adapalene gel was Differin (produced by Galderma), and there are some generic versions too. There are also higher strengths (e.g. 0.3%) and cream and lotion versions, which are prescription-only.

And because it is more chemically stable thanks to those aromatic rings, you can layer it with benzoyl peroxide without worrying about encapsulation. You can also get it combined with benzoyl peroxide in the one product (Epiduo is 0.1% adapalene and 2.5% benzoyl peroxide, Epiduo Forte has the adapalene bumped up to 0.3% – there are also generic versions).

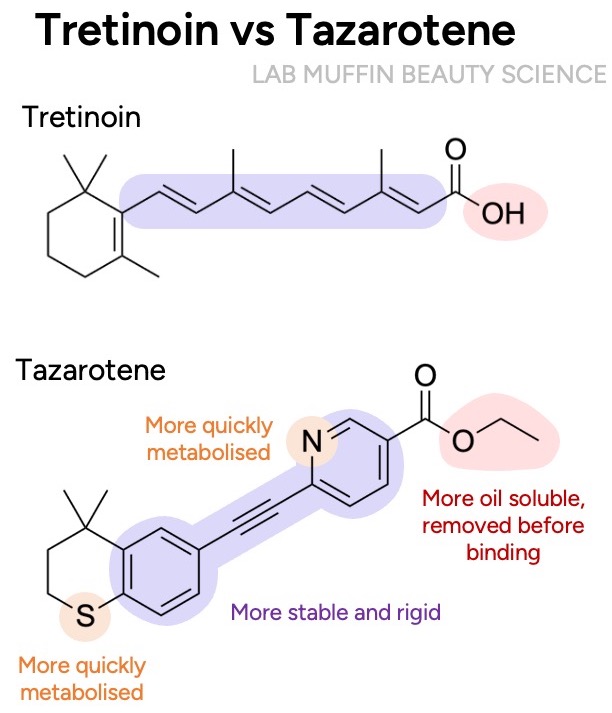

Tazarotene

Tazarotene was approved in 1997 for treating acne and plaque psoriasis:

Again there are aromatic rings for stability and rigidity, but we also have nitrogen and sulfur atoms, which were added for safety – they help your body get inactivate it faster, if it absorbs into blood. In theory, these should also make it less irritating, but that didn’t really pan out.

Tazarotene is interesting because it’s a prodrug – it’s inactive, and the ethyl group on the right of the molecule is removed by enzymes in skin to turn it into its active form, tazarotenic acid (it’s pretty fast and happens within minutes). A very common misconception I’ve often seen (including from a dermatologist on the Differin website!) is that drug retinoids are more effective because they’re already in the active form, and don’t need to be metabolised to work – but tazarotene is actually inactive, and considered by many to be the “strongest” drug retinoid.

Concentrations and formats

Tazarotene tends to be a bit more difficult to find than adapalene or tretinoin, but there are some interesting formulas:

- It’s usually found at 0.1%, but 0.045% and 0.05% are around as well

- Gel and cream formulas are more common, but there’s a 0.1% foam (Fabior) that absorbs faster and is easier to apply

- A newer 0.045% tazarotene lotion (Arazlo) contains a polymeric emulsion to distribute tazarotene and hydrating ingredients (mineral oil, sorbitol, diethyl sebacate) onto skin more uniformally and help delivery. In a manufacturer-funded study, it caused less irritation and was more effective than 0.1% tazarotene cream (Tazorac).

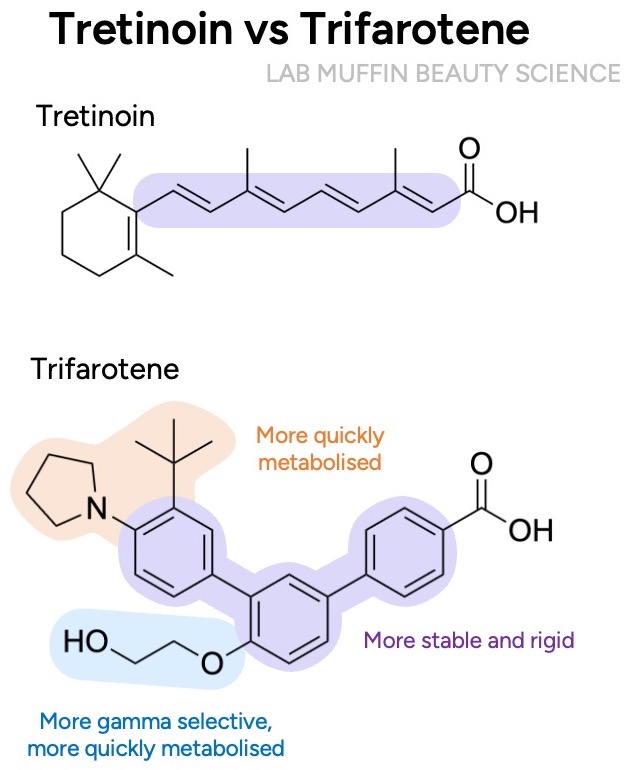

Trifarotene

Trifarotene is a fourth-generation retinoid, approved in 2019:

It was purposely designed to be even more selective for gamma RARs – the chain attached to the middle ring doesn’t fit as well into beta and alpha RARs, so it has 20-fold lower affinity for them. The reasoning was, again, that maybe even more selectivity would decrease side effects.

I’m not sure the logic really works, since adapalene and tazarotene are both more selective for beta than gamma, and we know their real-use irritation potentials went in opposite directions. But work was started on trifarotene in the mid-1990s before that was really established, and it could still have lower irritation due to its other properties.

More interestingly, trifarotene was also purposely designed to be safer. The attachments on the rings make it easier for the liver to inactivate trifarotene, should it absorb into blood. That’s why it’s specifically approved for treating body (truncal) acne – there’s a larger margin of safety, so it can be recommended for application to a larger surface area.

Related post: US Sunscreens Aren’t Safe in the EU? The Science

Trifarotene is also a lot more potent than the other retinoids, which is why it’s used at a much lower concentration of 0.005%. Because it’s so new, there’s only one brand-name formulation available at the moment: Aklief, a 0.005% trifarotene cream which contains a polymer that spreads out the actives evenly, and allantoin (anti-irritant).

Differences between retinoids

Before we get into the specifics of which retinoid is best for what, a few notes on some common misconceptions about their differences…

Receptors

Since they all work primarily by activating gamma retinoid receptors, it seems like all retinoids are likely to help with the common retinoid skin benefits like treating acne, fine lines, and excess pigment. Like for irritation, there’s been speculation about which receptor subtype works best for what, and again, it just wouldn’t make any sense – any differences seem to be more about where the ingredients end up in the skin, the concentrations and the formulations available.

Approved indications and clinical trials

Not all retinoids are approved to treat everything, and not all retinoids have clinical trials to back up particular benefits. Approved indications and clinical trials are helpful indications of how much data there is, but just like with the data for retinol, it’s important to remember the context – lack of data doesn’t mean lack of efficacy.

Drug companies actually need to collect and submit data to get a drug approved for a particular indication, which is an expensive process. And because drug approvals take into account the existing treatments and public need, not every benefit is as easy to get approved. Drug approval also differs by region. The limits of drug approvals are pretty well recognised – it’s why doctors are allowed to prescribe medications “off-label” (for benefits that aren’t officially approved).

For clinical trials, many of the issues mentioned in the retinol post also apply. Not every clinical trial has the same chance of getting funded, done and published. And when a drug is approved for a particular condition, that tends to get studied more in clinical trials.

Tretinoin was the first to be discovered, so it’s been approved and studied for more indications than the other three retinoids. But even then, there’s some unusual contextual stuff that happens – for example, some brands of tretinoin are approved for photoaging but others aren’t. And comparative trials usually find that the newer retinoids can perform better for some indications, despite there being less clinical trials on them (although there’s likely some publication bias there too, since the trials are often funded by companies promoting competitor products).

Irritation

From least to most irritating, the general trend seems to be adapalene < tretinoin < tazarotene. The jury is out on trifarotene, but so far it seems to be on the less irritating end.

There’s a misconception that irritation and benefits go hand-in-hand for retinoids, and efficacy matches irritation (adapalene < tretinoin < tazarotene), but this isn’t borne out by the evidence:

- Efficacy mostly comes from the ingredient acting on RARs, whereas irritation can be improved or worsened by non-RAR effects (e.g. pain receptors, mast cell activation, as discussed in this post)

- Clinical trials on acne have generally found that 0.1% adapalene gel is about as effective as 0.025% tretinoin, but with less irritation

Which retinoid?

It’s always best to consult a dermatologist about which product best suits your needs and situation. But here’s some general information (thanks to XX and XX for checking this!)

Acne

All of the retinoids are approved to treat acne – it seems to be a lower bar for getting a retinoid approved (probably because bigger differences can be measured in a shorter timeframe).

Adapalene is particularly helpful for acne treatment, since it’s stable to benzoyl peroxide and the particle size is tailored to targeting the hair follicles (at least in the original Differin formulation). The OTC availability in some countries also makes this easier to access.

Trifarotene is officially approved for treating truncal acne due to its greater margin of safety, but there’s limited access and there aren’t any generics.

Tretinoin is more irritating, and unstable with benzoyl peroxide, but it’s probably the easiest drug retinoid to access.

Comparative studies have sometimes found that tazarotene is slightly more effective for acne than other retinoids, but irritation might be a problem.

Wrinkles, texture

Tretinoin and tazarotene are approved for signs of photodamage (e.g. fine wrinkling, skin roughness). There are studies finding improvements in other types of uneven texture like pores and acne scars, which makes sense since how they’re thought to work (increasing collagen, normalising elastin, increasing glycosaminoglycans) should help with other types of uneven texture too.

Adapalene isn’t approved for any anti-aging claims, but there is a clinical trial from 2018 that found that 0.3% adapalene gel is comparable to 0.05% tretinoin cream for photoageing, including for periorbital and forehead wrinkles.

Pigment

Both tretinoin and tazarotene are approved for mottled hyperpigmentation, and there are studies that have found that they work for other types of pigmentation too. There are several studies on tretinoin and tazarotene decreasing post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation after acne, including in darker skin, although irritation can cause rebound PIH. The newer, less irritating 0.045% tazarotene lotion seems to be tailored to reduce this risk.

Adapalene isn’t approved for pigment treatment, but a few studies have had promising results. The 2018 clinical trial on 0.3% adapalene gel and photoaging found that it decreased hyperpigmentation and freckles. Another study found that 0.1% and 0.3% adapalene lightened sunspots. One tazarotene-manufacturer-funded study found that 0.3% adapalene does seem to reduce PIH, but not as well as 0.1% tazarotene.

Trifarotene did reduce and prevent hyperpigmentation in animal models during development, but no clinical studies have been published yet.

Where to start

Adapalene is one of the best beginner options since it’s available over-the-counter in some places, and irritation is the biggest problem for most people starting on retinoids.

Tretinoin is another good starting option for most people, mostly due to its widespread availability and how well-studied it is, although irritation and stability are issues.

Tazarotene’s higher irritation means it’s usually recommended after people have used retinoids before.

Trifarotene might be a good but less studied option, with limited availability.

A lower concentration of an active will generally give less irritation, although this still depends on formulation.

Converting percentages

Converting between percentages of different retinoids is pretty iffy – the clinical studies usually compare commercially available concentrations, and as newer formulations with lower concentrations have come out (tretinoin microsponge, 0.045% tazarotene), it’s become clear that some of the available concentrations weren’t actually the lowest effective doses, and formulation makes a big difference too.

In general:

- Trifarotene is only found at 0.005%, tazarotene is only commonly found at 0.1% but the newer 0.045% lotion claims to be more effective than 0.1%

- For acne, 0.1% adapalene gel is most studied, and has generally been found to be slightly more effective or similar to 0.025% tretinoin gel

- One clinical trial found that 0.3% adapalene gel is comparable to 0.05% tretinoin cream for photoageing

- 0.1% tazarotene cream worked better than 0.05% tretinoin cream for photodamage in one study

References

Thanks to Ruby for helping factcheck this post, and adding some info on the formulations available!

Good general references on retinoids:

- Baumann LS. Retinoids. In: Baumann LS, Rieder EA, Sun MD, eds. Baumann’s Cosmetic Dermatology. 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill; 2022:615-630.

- Sorg O, Kaya G, Saurat JH. Topical Cosmeceutical Retinoids. In: Draelos ZD, ed. Cosmetic Dermatology: Products and Procedures. 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons; 2023:408-419.

Kligman AM. The growing importance of topical retinoids in clinical dermatology: a retrospective and prospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Pt 3):S2-S7. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70437-2

Griffiths CE, Kang S, Ellis CN, et al. Two concentrations of topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) cause similar improvement of photoaging but different degrees of irritation. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled comparison of 0.1% and 0.025% tretinoin creams. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(9):1037-1044. DOI: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690210067011

Macgregor JL, Maibach HI. Specificity of Retinoid-Induced Irritation and Its Role in Clinical Efficacy. In: Zhai H, Wilhelm KP, Maibach HI, eds. Dermatotoxicology. 7th ed. CRC Press; 2008:423-430. (The earlier version of this article is doi:10.1159/000058335)

Olsen EA, Katz HI, Levine N, et al. Tretinoin emollient cream for photodamaged skin: results of 48-week, multicenter, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 Pt 1):217-226. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80128-4

Veraldi S, Barbareschi M, Benardon S, Schianchi R. Short contact therapy of acne with tretinoin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(5):374-376. doi:10.3109/09546634.2012.751085

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Multi-disciplinary Review and Evaluation NDA 209353. February 1, 2016.

Kircik LH, Draelos ZD, Berson DS. Polymeric Emulsion Technology Applied to Tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(4):s148-s154.

Lucky AW, Cullen SI, Jarratt MT, Quigley JW. Comparative efficacy and safety of two 0.025% tretinoin gels: results from a multicenter double-blind, parallel study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(4):S17-S23. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70141-0

Del Rosso J, Sugarman J, Green L, et al. Efficacy and safety of microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide and microencapsulated tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Results from two phase 3 double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(4):719-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.05.093

Berson DS, Shalita AR. The treatment of acne: the role of combination therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 3):S31-S41. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90418-2

Sitohang IBS, Makes WI, Sandora N, Suryanegara J. Topical tretinoin for treating photoaging: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8(1):e003. Published 2022 Mar 25. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000003

Rendon M, Berneburg M, Arellano I, Picardo M. Treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl 2):S272-S281. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.039

Bouloc A, Vergnanini AL, Issa MC. A double-blind randomized study comparing the association of retinol and LR2412 with tretinoin 0.025% in photoaged skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14(1):40-46. doi:10.1111/jocd.12131

Dosik JS, Homer K, Arsonnaud S. Cumulative irritation potential of adapalene 0.1% cream and gel compared with tretinoin microsphere 0.04% and 0.1%. Cutis. 2005;75(4):238-243.

Culp L, Moradi Tuchayi S, Alinia H, Feldman SR. Tolerability of Topical Retinoids: Are There Clinically Meaningful Differences Among Topical Retinoids?. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19(6):530-538. doi:10.1177/1203475415591117

Bernard BA. Adapalene, a new chemical entity with retinoid activity. Skin Pharmacol. 1993;6 Suppl 1:61-69. doi:10.1159/000211165

Shroot B, Michel S. Pharmacology and chemistry of adapalene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 2):S96-S103. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70050-1

Shroot B. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of topical adapalene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Pt 3):S17-S24. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70440-2

Allec J, Chatelus A, Wagner N. Skin distribution and pharmaceutical aspects of adapalene gel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 2):S119-S125. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70055-0

Verschoore M. Overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 2):S91. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70048-3

Martin B, Meunier C, Montels D, Watts O. Chemical stability of adapalene and tretinoin when combined with benzoyl peroxide in presence and in absence of visible light and ultraviolet radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139 Suppl 52:8-11. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s2008.x

Czernielewski J, Michel S, Bouclier M, Baker M, Hensby JC. Adapalene biochemistry and the evolution of a new topical retinoid for treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15 Suppl 3:5-12. doi:10.1046/j.0926-9959.2001.00006.x

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves Differin Gel 0.1% for over-the-counter use to treat acne. Published 2016. Accessed November 10, 2023.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Cross Discipline Team Leader Review 020380Orig1s010. June 9, 2015.

Dunlap FE, Mills OH, Tuley MR, Baker MD, Plott RT. Adapalene 0.1% gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: its superiority compared to tretinoin 0.025% cream in skin tolerance and patient preference. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139 Suppl 52:17-22. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s2017.x

Cunliffe WJ, Poncet M, Loesche C, Verschoore M. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.1% gel versus tretinoin 0.025% gel in patients with acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis of five randomized trials. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139 Suppl 52:48-56. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s2048.x

Millikan LE. Adapalene: an update on newer comparative studies between the various retinoids. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(10):784-788. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00050.x

Bagatin E, Gonçalves HS, Sato M, Almeida LMC, Miot HA. Comparable efficacy of adapalene 0.3% gel and tretinoin 0.05% cream as treatment for cutaneous photoaging. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(3):343-350. doi:10.1684/ejd.2018.3320

Kang S, Goldfarb MT, Weiss JS, et al. Assessment of adapalene gel for the treatment of actinic keratoses and lentigines: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1):83-90. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.451

Leyden J, Grove GL. Randomized facial tolerability studies comparing gel formulations of retinoids used to treat acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2001;67(6 Suppl):17-27.

Greenspan A, Loesche C, Vendetti N, et al. Cumulative irritation comparison of adapalene gel and solution with 2 tazarotene gels and 3 tretinoin formulations. Cutis. 2003;72(1):76-81.

Dosik JS, Homer K, Arsonnaud S. Cumulative irritation potential of adapalene 0.1% cream and gel compared with tretinoin microsphere 0.04% and 0.1%. Cutis. 2005;75(4):238-243.

Chandraratna RA. Tazarotene-first of a new generation of receptor-selective retinoids. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135 Suppl 49:18-25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb15662.x

Lowe N, Gifford M, Tanghetti E, et al. Tazarotene 0.1% cream versus tretinoin 0.05% emollient cream in the treatment of photodamaged facial skin: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2004;6(2):79-85. doi:10.1080/14764170410032406

Kang S, Leyden JJ, Lowe NJ, et al. Tazarotene cream for the treatment of facial photodamage: a multicenter, investigator-masked, randomized, vehicle-controlled, parallel comparison of 0.01%, 0.025%, 0.05%, and 0.1% tazarotene creams with 0.05% tretinoin emollient cream applied once daily for 24 weeks. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(12):1597-1604. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.12.1597

Smith JA, Narahari S, Hill D, Feldman SR. Tazarotene foam, 0.1%, for the treatment of acne. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(1):99-103. doi:10.1517/14740338.2016.1117605

Draelos ZD. Low irritation potential of tazarotene 0.045% lotion: Head-to-head comparison to adapalene 0.3% gel and trifarotene 0.005% cream in two studies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34(1):2166346. doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2166346

Webster GF, Guenther L, Poulin YP, Solomon BA, Loven K, Lee J. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized comparison study of the efficacy and tolerability of once-daily tazarotene 0.1% gel and adapalene 0.1% gel for the treatment of facial acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2002;69(2 Suppl):4-11.

Tanghetti E, Dhawan S, Green L, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(5):549-558.

Ogden S, Samuel M, Griffiths CE. A review of tazarotene in the treatment of photodamaged skin. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(1):71-76. doi:10.2147/cia.s1101

Afra TP, Razmi T M, Narang T, Dogra S, Kumar A. Topical Tazarotene Gel, 0.1%, as a Novel Treatment Approach for Atrophic Postacne Scars: A Randomized Active-Controlled Clinical Trial. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21(2):125-132. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2018.1404

Grimes P, Callender V. Tazarotene cream for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne vulgaris in darker skin: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2006;77(1):45-50.

Tanghetti EA, Kircik LH, Green LJ, et al. A Phase 2, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Clinical Study to Compare the Safety and Efficacy of a Novel Tazarotene 0.045% Lotion and Tazarotene 0.1% Cream in the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Acne Vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):542.

Tanghetti EA, Werschler WP, Lain E, et al. Novel Polymeric Lotion Formulation of Once-Daily Tazarotene (0.045%) for Moderate-to-Severe Acne: Pooled Phase 3 Analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(3):272-279. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.4869

Bader K. Tazarotene 0.045% Lotion for Acne Safe, Improves Hyperpigmentation in SOC Patients. Dermatology Times. June 12, 2023. Accessed December 6, 2023.

Thoreau E, Arlabosse JM, Bouix-Peter C, et al. Structure-based design of Trifarotene (CD5789), a potent and selective RARγ agonist for the treatment of acne. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28(10):1736-1741. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.036

Aubert J, Piwnica D, Bertino B, et al. Nonclinical and human pharmacology of the potent and selective topical retinoic acid receptor-γ agonist trifarotene. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):442-456. doi:10.1111/bjd.16719

Callender VD, Baldwin H, Cook-Bolden FE, Alexis AF, Stein Gold L, Guenin E. Effects of Topical Retinoids on Acne and Post-inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients with Skin of Color: A Clinical Review and Implications for Practice. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(1):69-81. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00643-2

Thank you for this! I used Retin-A back in the eighties and nineties to treat teenage acne, and just cheerfully restarted it because I get a zit occasionally thanks to perimenopause. Will use it on my neck and chest now as it breaks down quickly, might as well get a new tube sooner and refresh my skin! Thanks so much 🙂

Hi Michelle! Thank you for all your amazing content. I have a question. If one can tolerate tretinoin (say at 0.025%) for daily use, is there any benefit to using an OTC retinol instead? I’ve been interested in trying Ultraceuticals Vitamin A, but is there any sense in that or better to just stick with tret? Thank you!