In case you haven’t already heard, the 2021 edition of “This Anti-Cancer Product Is Giving You Cancer” is that there’s been benzene found in a bunch of sunscreens. How much should we be freaking out about this?

I did an Instagram post on this already, but I thought I’d elaborate a bit more. The video is here on YouTube, scroll down for the text version.

Benzene in Sunscreens

First, let’s talk about the results before we go into some of the more questionable things about this report. It’s from Valisure, a US-based online pharmacy that brands themselves as “The Pharmacy That Checks”. The premise is, FDA doesn’t regulate drugs as well as Valisure think they should, so they test drugs before selling them through their pharmacy.

Valisure bought sunscreen and after sun care products from 294 batches from 69 different brands, and sent them to some labs for gas chromatography. They found benzene at low ppm concentrations in 78 of these – mostly spray sunscreens and after sun products. There was over 2 ppm in 14 batches, between 0.1 and 2 ppm in 26 batches, and the rest had below 0.1 ppm (216 batches had no detected benzene). For reference, 2 parts per million is about 1/150th of a drop of benzene in a 150 mL (5 fl oz) tube, or 1/300th of a drop in a 75 mL tube.

Valisure picked 2.0 ppm because it’s the limit that the FDA recommends in hand sanitisers and medications. Attachment A also has the list of sunscreens tested that didn’t have benzene detected in them.

I’ve seen a lot of stuff online about this – let’s clear a few things up.

Benzene is not purposely added to products

Firstly, no one is purposely adding benzene as an ingredient to products. It’s not a fragrance, it’s not a preservative, it doesn’t protect against UV well enough to be a sunscreen – it has no beneficial function that isn’t more cheaply and easily achieved with a different ingredient.

Benzene is a trace contaminant. It’s in there because it’s an impurity in another ingredient, or because of something happening in the manufacturing process.

Benzene contamination is not specific to sunscreens

It’s also not an issue specific to sunscreens – there are also after-sun aloe vera gel products listed in the highest benzene group, and an earlier report also found it in hand sanitisers.

It has nothing to do with chemical sunscreens

It’s not because of particular sunscreen ingredients or chemical sunscreens. Both chemical and mineral sunscreens show up on the list, and Valisure also checked samples of raw sunscreen ingredients for benzene. There are some sunscreen ingredients that have names that look like the word benzene, but they’re not the same thing, like how Lady Gaga has very little to do with Galileo Galilei.

It also isn’t a problem with particular brands – all of the brands with benzene above 2 ppm also had products with no detected benzene, apart from the brand that only had one product tested.

And it’s not specific to particular products – there were several batches tested of the one sunscreen product, and they had very different concentrations of benzene. So it seems like sometimes when they made the product there was more benzene, and sometimes when they made the same product there wasn’t as much.

So if you want to find out if a sunscreen you have is one of the ones with benzene, you don’t just have to match the name of the product – you also want to check the UPC, Lot and expiry date and make sure everything matches to see if you have an affected product. There are also four lists, so make sure you’re looking at the right list – if you look at the whole row, the amount of benzene is near the far right (“ND” is means benzene was not detected).

But how worried exactly should we be about benzene?

There are two phrases in the report that I think were misinterpreted that make benzene sound scarier than it is: benzene is a “known human carcinogen” and there’s “no safe level” of benzene. And this sounds like anyone who’s had any exposure to benzene has upped their chances of developing cancer by a lot. But that’s not really true.

Related post: Octocrylene Causes Cancer? and I’m Propaganda Now (with video)

“Known Human Carcinogen”

“Known human carcinogen” is a classification by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. These classifications – known/probable/possible human carcinogen – tell us how certain the evidence is that something increases the risk of cancer. It doesn’t tell us how big the increase is. So things that are really potent are in the same category as things that are really weak, which can lead to unjustified fearmongering. For example, we know that walking near a dog definitely increases your risk of getting bitten by a dog, and punching a dog does as well, so they’re both “known dog-bite causes” – but one of them is much worse.

We can see this from looking at some of the other known carcinogens: smoking tobacco and eating processed meat. I think we all know that there’s a big difference in cancer risk between smoking cigarettes and eating a few slices of salami. And on top of that, there’s also a big difference in cancer risk between smoking one cigarette once when you were 16 and smoking 30 cigarettes a day for 50 years.

You might remember the idea of hazards versus risks from my post about clean beauty. These classifications essentially are hazard-based.

Related post: Clean Beauty Is Wrong and Won’t Give Us Safer Products

“No Safe Level”

The other phrase that I think got taken out of context is that there’s “probably no safe level” of benzene. Combined with “known human carcinogen”, it really sounds like any amount of benzene exposure is going to increase your chance of cancer to a dangerous level.

But the rest of the sentence is: “there is likely no safe level of exposure to benzene and that all exposures constitute some risk in a linear, if not supralinear, and additive fashion”. In this toxicological context, “safe” is when there’s absolutely zero effect. “No safe level” means that small exposures can add up.

But the important question is: how much does the amount in sunscreen add to the benzene what we’re already getting?

Background exposure to benzene

As a few of us pointed out on Instagram, we’re actually exposed to benzene quite a bit in our everyday lives. So we need to think about that to contextualise how much extra we’re getting from sunscreen.

Inhalation

We mostly get benzene by inhaling it – for example, petrol (or gasoline if you’re American) has about 1-3% benzene in it these days. For comparison, this converts to 10 000 to 30 000 ppm. Cigarette smoke and bushfires also produce benzene, and we also get it from indoor fumes – there’s tiny bits of benzene left over from manufacturing plastics and other household products that will slowly be released over time. We also eat it in food and it’s in drinking water.

But these amounts that we get in everyday life aren’t enough to lead to cancer. The link to cancer is with much higher amounts: industrial exposures where workers are working with benzene every day. For the general population, we usually inhale 3 to 40 micrograms per cubic meter, which is a thousand times less than the amount that’s been found to be problematic and linked to cancer.

Skin absorption

Unfortunately there isn’t as much information on skin contact like you’d get with sunscreens, since industrial exposures are mostly via inhalation, and the main concern with benzene is industrial exposure. Benzene is volatile, so a lot of it evaporates off your skin instead of absorbing through skin to get into your body. How much gets through depends a lot on what else the benzene is mixed with. In general, it’s a fraction of a percent of the amount you put on, and not all of the stuff that absorbs through skin actually makes it to your blood.

One paper estimated that placing a worker’s hands and lower forearms in 0.1% (1000 ppm) benzene for an hour a day for 40 years with a damaged skin barrier (higher than normal absorption) would result in a relative risk of leukemia of 1.42 (i.e. they’d be around one and a half times more likely to develop leukemia than if they just had regular exposure to benzene). But if 0.01% (100 ppm) benzene was used instead, there would be close to no increased risk of leukemia (relative risk of 1.03). So 100 ppm is the limit recommended for solvents for workers.

The highest amount found by Valisure in sunscreens was 6 ppm, so based on the evidence, it seems like it’s not going to make much of a difference. Joe Schwarcz, a chemistry professor and professional debunker says the same – he thinks “the chance that that [benzene applied in sunscreen] leads to any significant amount in the blood is infinitesimal.”

Now don’t get me wrong – benzene is harmful and there’s no benefit from it, so we should reduce our exposure to benzene, and it’s definitely a good thing that regulators have been working on reducing exposure. But like with other harmful or hazardous things, the risk depends on the exposure. The harm depends on how much you have of it, and how you’re exposed to it. And this aspect gets lost a lot of the time.

I’ve talked about this with “dirty” lists from clean beauty before, but it’s happened so many other times before clean beauty came along. For example, with lead in lipstick in the early 2000s – there are trace amounts of lead in lipstick and there’s nothing beneficial about lead, but the amount is so small that it doesn’t have any real effect on your health.

Shifty framing?

There are a few things included the Valisure report that I find confusing.

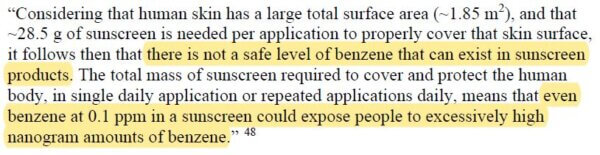

The dermatologist quoted as an expert says that “there is not a safe level of benzene that can exist in sunscreen products” and that “even benzene at 0.1 ppm in a sunscreen could expose people to excessively high nanogram amounts of benzene”. I don’t think this reflects what we know about the toxicology of benzene.

“No safe level” (again)

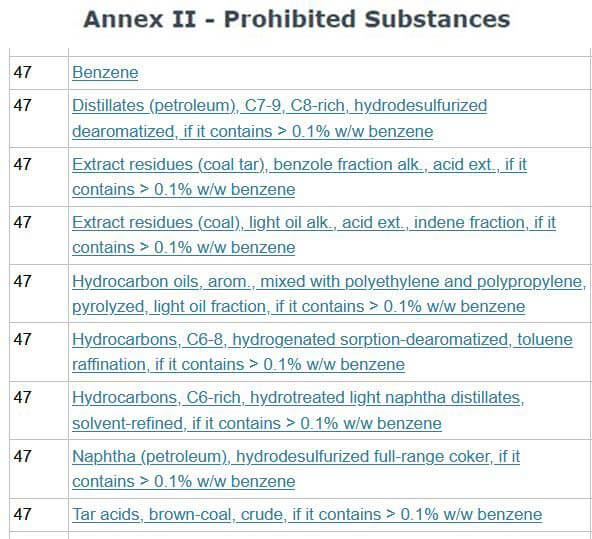

For example, in the EU, benzene is allowed in cosmetics as an impurity in some ingredients if it’s below 0.1% w/w (which is equivalent to 1000 ppm).

If they had near 1000 ppm benzene in the ingredient, it would have to be used at less than 0.01% to give a final benzene concentration below 0.1 ppm. But they’re used at way higher percentages than that, so EU toxicologists clearly think there’s a safe level that’s above 0.1 ppm.

“Nanograms”

The “excessively high nanogram amounts of benzene” bit is also weird, since we’re exposed to much higher amounts every day that we’d measure in micrograms, not nanograms. A 2010 paper estimated that non-smokers inhale around 200 to 450 micrograms (200 000 to 450 000 nanograms) of benzene a day – and of course this is well below the industrial exposures linked to cancer.

Weird NDMA comparison

There’s also a really scientifically dicey comparison in the report. There’s another not-very-nice substance, N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA, not MDMA) that’s been found in some pills (not those pills). The FDA has limited NDMA to around 2 ppm, which translates to a maximum dose of 96 ng a day. So they use this as a “comparable benchmark” for the amount of benzene you’d get from 4 shot-glasses of sunscreen at 2 ppm.

This comparison is really wack for a lot of reasons – obviously we apply a lot more sunscreen than a tablet, so the same concentration doesn’t give the same dose (one caffeine tablet can’t be compared to 4 shot glasses of caffeine tablets, even though the caffeine concentration is the same per tablet). So if they were allowed at the same concentration, then benzene is considered a lot safer.

That’s in addition to the fact it’s also a completely different route of exposure. We swallow tablets, we don’t swallow sunscreen (well I hope you don’t, anyway) – so again, it’s a silly comparison.

Melodramatic disposal recommendations

There’s also the disposal recommendations.

Valisure say you should dispose of contaminated sunscreens as hazardous waste, but as an environmental scientist who works in hazardous waste pointed out, these are absolutely minuscule amounts of benzene (again, 1/150th of a drop in a 150 mL tube). Hazardous waste people will probably be really confused if you ask them about it. The fact that aerosol sprays are flammable is probably a much bigger issue.

Final thoughts

Again, I think benzene is harmful, and reducing exposure is good. But hopefully this gives some context so you can decide how anxious you should be about potential benzene exposure from sunscreens that you’ve been using, or that haven’t been tested yet. Also note that benzene in personal care products has never been linked to cancer, but UV exposure definitely has.

I would personally stop using the products from batches that were measured to have high amounts of benzene for now (but I would still hold onto them in case of recall or more information).

Will the FDA actually issue a recall? I think Joe Schwarcz is right – based on the evidence it does seem scientifically unjustified, but governments do a lot of scientifically unjustified things.

Related post: Is Your Sunscreen Killing Coral Reefs? The Science (with Video)

(Special thanks to Stephen for his invaluable feedback (and convincing me to make this video), and @wasabi.gif for her insights!)

References

American Cancer Society, Known and Probable Human Carcinogens, 14 Aug 2019

Boobis AR, Cohen SM, Dellarco VL, et al., Classification schemes for carcinogenicity based on hazard-identification have become outmoded and serve neither science nor society (open access), Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 82, 158-166. DOI: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.10.014

Smith MT, Advances in understanding benzene health effects and susceptibility (open access), Annu Rev Public Health 2010, 31, 133-148. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103646

Schwarcz J, Benzene in your car – and it’s not in the gas tank! McGill Office for Science and Society, 20 Mar 2017

Williams PR et al., Dermal absorption of benzene in occupational settings: estimating flux and applications for risk assessment, Crit Rev Toxicol 2011, 41, 111-142. DOI: 10.3109/10408444.2010.530224

Kalnas J, Teitelbaum DT, Dermal absorption of benzene: implications for work practices and regulations, Int J Occup Environ Health 2000, 6, 114-121. DOI: 10.1179/oeh.2000.6.2.114

Salviano Dos Santos VP et al., Benzene as a Chemical Hazard in Processed Foods (open access), Int J Food Sci 2015, 545640. DOI: 10.1155/2015/545640

A great take on the topic, thank you for sharing more about the toxicologic part of the issue.

What do you think about the app Yuka, which tells you which skin and food products are healthy and not? Is this another ‘clean beauty’ myth? I have been refusing to buy products I used to like because they show up as ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ on Yuka, such as La Roche Posay’s Anthelios spray sunscreen because they have nanoparticles. Are these really that dangerous? I live in London, England, and only use sunscreen on sunny days because we get so little sunlight here anyway. In fact we are told to take Vitamin D most days as most people don’t get enough sunlight here. Your thoughts are greatly appreciated.

It sounds like a dodgy app – nanoparticles are fine, there’s a really good review of them from the Australian TGA: https://www.tga.gov.au/literature-review-safety-titanium-dioxide-and-zinc-oxide-nanoparticles-sunscreens

Excellent article. Although you didn’t say this directly, my takeaway lesson is that my risk of skin cancer from sun exposure without sunscreen will be much higher than my risk of cancer from the benzene in sunscreen. My risk of skin cancer is different from anyone else. For example, my risk is influenced by the fact that I am 53 years old, a very pale Caucasian woman who grew up without sunscreen and I have been sunburned too many times to count, some even when wearing sunscreen. I am sure there’s a mathematical model that can determine risk at this point in time, but it would likely change over time.

Thanks Michelle

Are there any sources for the list of contaminated products, not behind a paywall?

Yes, the Valisure site has the PDFs without a paywall.

I admit that I’m not a great math talent, but this strikes me as backwards:

“2 parts per million is about 1/150th of a drop of benzene in a 150 mL (5 fl oz) tube, or 1/300th of a drop in a 75 mL tube.” I’m pretty sure that the 75 mg tube has half the amount of benzene (right?), and that 1/300th is half of 1/150th (right?), so the 150mL tube has twice as much benzene (right?).

I drink a lot of soda, and it contains citric acid and sodium benzoate, which I believe make benzene, and it’s always astonished me that that’s allowed. (These two don’t just appear in soda, either, but in lotsa foods.) I gather I just can’t escape benzene, can I? 🤕 Sigh.

Thanks for letting me know I needn’t worry about sunscreen by itself, Michelle. (I’ll instead worry about the many things I ingest and rub on my body all taken together!)

I am writing an article for EuroCosmetics Magazine and would like to quote you from this article. Would that be permissible? I am on deadline so, thanks for your kind response. I am absolutely delighted to have found you in my search. I concur with your POV. Thank you. I will also try to Link In with you. I think we have many synergies only I am not a PhD in chemistry. I have worked with patients in dermatology for years.

Yes that’s fine!