Recently you might have heard that one of my former favorite sunscreens Purito Centella Unscented Sun tested at SPF 19, which is much lower than its labeled protection of SPF 50+. There were rumours that it didn’t match the label claim before, but until INCI Decoder published the two in-vivo SPF tests on their blog, a lot of scientists were saying that there wasn’t enough evidence yet to disbelieve the label.

This sort of thing has happened with all sorts of sunscreens from all over the world before, from both big and small brands – where later testing didn’t get the SPF that’s claimed on the label.

There is the possibility of the newer test being wrong and the label being correct, and I’ll go into some of the possible reasons for this later on. But I think most people now feel like there is enough evidence to be more cautious.

Purito put out a statement saying they’ve paused the sale of their sunscreens, and they said that they actually sent off their sunscreens for a test earlier but they still haven’t gotten the results yet.

So were we all wrong to say the labeled SPF was the best data point we had? Should we stop trusting all Korean sunscreens, or Asian sunscreens? Should we only use sunscreens from large Western manufacturers? Why did cosmetic formulators and scientists who understand sunscreen wait till there were two in vivo SPF tests before saying anything?

Hopefully this will give you more insight into the whole situation and why SPF testing is so darn tricky.

The video is here on YouTube, keep scrolling for the written version…

How is SPF tested?

Let’s start with how SPF testing is done.

Related post: What Does SPF Mean? The Science of Sunscreen

In short, SPF measures how much protection you get from erythemal or sunburn-causing UV from a sunscreen, or any other product.

SPF tests are done by putting 2 milligrams per square centimetre of sunscreen on the backs of human volunteers. A special UV lamp is shone onto the backs, and how much UV the skin can take with and without the sunscreen is compared.

There are a lot of really annoying things about this test. Anything that involves human volunteers is a lot more expensive than if you just have to use a machine – it’s somewhere in the region of $5000 to 10000 USD for a test, and if the first version of your sunscreen doesn’t give you a high enough or consistent enough SPF, then you have to repeat this again and again until you get it. And you’re harming people with this test.

The sun care industry has been working for a long time to find an alternative way of testing SPF. But the main issue that keeps coming up is that it’s really hard to mimic how sunscreen reacts with human skin.

Human skin is bumpy and so if you have a thicker sunscreen, then some of it might not get into the grooves and you might have little bits of hills sticking up. Sunscreens also dry on skin in a particular way which might be different from drying on glass, or on different types of plastic.

So both the international standard test for SPF labelling (the ISO 24444 test) and the FDA test (which is very similar) still use in vivo tests on actual human beings. This applies to most places worldwide, including the US, South Korea and Australia.

There are little differences between the regions with things like how reproducible the test has to be, and how many volunteers you have to use, but in essence the test is the same.

So why are we still doing this annoying test? Can’t we work out SPF in other ways? Let’s talk about the issues with alternative methods.

SPF from ingredients list?

Why can’t you work out the SPF from the ingredients list?

Sunscreens are annoyingly complicated. The saying that the ingredients list can’t tell you the whole story about how a product works is especially applicable to sunscreens.

Cosmetic formulators know this really well, because sunscreens are one of the hardest things to formulate. It can take months to finish a sunscreen.

One cosmetic chemist told me that she just finished formulating a sunscreen, and it took her 6 months, even though she started with an SPF 30 base and just had to raise the SPF. So obviously protection isn’t just about the amounts of filters you put into it, because if it was then they’d be done in a day.

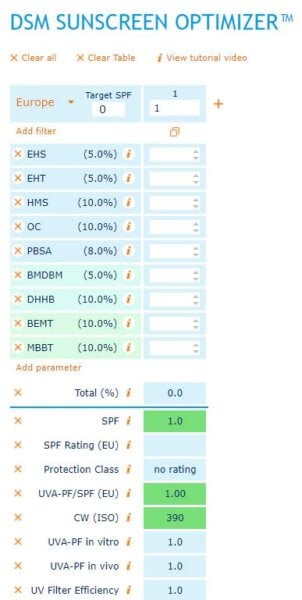

This nifty tool is the DSM Sunscreen Optimizer:

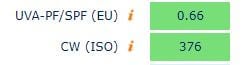

But they can give you an idea of what sorts of things will change your sunscreen protection, and how the absorbance over different wavelengths will change, but DSM and BASF make it very clear that these are just a starting point for formulation. If you put in the percentages from a bunch of real sunscreens you can see that the SPF predicted can be wildly off. So if these models can’t give you an accurate prediction, then just looking at the filters in a sunscreen isn’t going to be any better!

But I am going to use the Sunscreen Optimizer to demonstrate a few things…

The number of filters doesn’t tell you much

First off, with the number of filters in the sunscreen I’ve seen some influencers confidently say that you need more filters for so called “redundancy”, that every sunscreen needs to have more than two filters to give you a high SPF.

I think this idea comes from the observation that a lot of the sunscreens on the market with high SPF do have a lot of different filters. But having multiple filters in there doesn’t mean you actually need to have multiple filters in there to get a higher SPF. There are a lot of other explanations for why sunscreens often end up with multiple filters…

Firstly if your filters aren’t broad spectrum enough if they’re not covering a wide enough range of wavelengths, then you’re going to have to put in other filters in there to cover the rest. Something very broad spectrum like zinc oxide can be the only filter in a sunscreen.

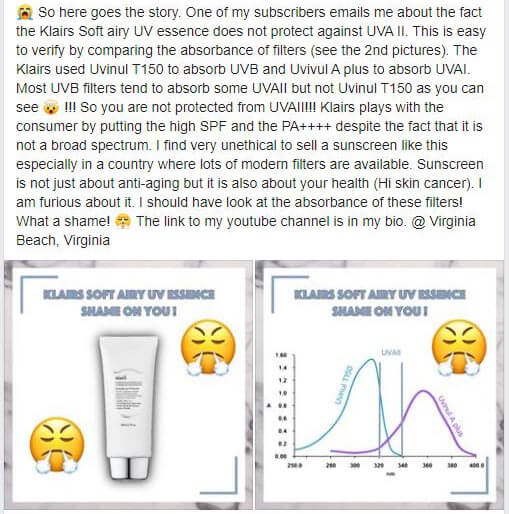

In the Purito sunscreen there are two filters, and some “science-based” bloggers have said that these two filters could not possibly give you a broad spectrum sunscreen, claiming there’s a dip in the UVA2 region because the two filters have peaks in the UVB and UVA1 regions:

But this a misunderstanding of how these filters (and really, any UV absorbers) work – it doesn’t mean that UVA2 isn’t covered enough, because both of these filters do absorb in the UVA2 region, and they can work together (additively and synergistically) in that region.

This is actually one of the things you can get a decent idea of with just the ingredients list. It can be confusing if you’re not used to interpreting these sorts of individual filter spectra, because it does sort of look like there’s a dip there. But you are meant to roughly add them together, and the computer model can do this – if you put in the percentages into the computer model (assuming these percentages are correct), you can see there is actually barely a dip in the UVA2 region, and it is actually predicted to be broad spectrum.

(These newer filters are excellent – the reason they’re not approved in the US is basically that the FDA is very slow at getting these new filters approved. They’ve recently reopened the case, but they’re asking for safety data based on animal testing and because of the animal testing ban, sunscreen companies can’t go and get this extra specific data. So there’s a bit of a stalemate in the US about approving these filters until newer non-animal tests are developed. But based on other safety data, they’ve been approved pretty much everywhere else including the EU and Australia.)

Sunscreen development is also really expensive and involves months of trial and error. So say if a particular brand had an SPF 30 formula they were really happy with, but they see that everyone’s moving towards SPF 50+ products now, they might choose to just add extra filters to their existing SPF 30 sunscreen instead of trying to start from scratch again. (This process can still take months and months.)

But if you add more of the filters you already had, you might exceed the regulatory limits, or they might solidify out (you get crystals in the sunscreen formula and it doesn’t work anymore). Adding different filters can get around this.

Newer filters tend to be more efficient over a wider range of wavelengths, so you don’t need as much to get higher protection and so you don’t necessarily hit that limit.

I think this is why we see a lot of sunscreens on the market where they have some really cool new filters, along with some older filters that people aren’t really that into anymore like octinoxate and oxybenzone, and that list doesn’t make a lot of sense if it was actually designed from scratch.

There’s also the cost of the sunscreen ingredient. If you want to cover the whole spectrum with one or two filters and you don’t want to go with a mineral sunscreen, then you pretty much have to use some of the newer broad spectrum filters.

These are more expensive and so, even though it’s theoretically possible to make a sunscreen with just Tinosorb S if you look at the computer model, it would be a lot more attractive to cut down on that expensive Tinosorb S and chuck in some cheaper filters instead.

There are also a few combinations of filters that work better together and so, combining them means that you can take advantage of that synergy.

Concentrations of filters?

So can we tell the SPF from the percentages of the filters?

Inactive ingredients influence SPF

One of the reasons that some people said Purito had to be lying is that there were low concentrations of the filters. The problem with this is that yes, the SPF does depend on the percentages of the filters… but also on a lot of other things, like how well the formula spreads out the sunscreen actives in the final sunscreen film, whether there’s SPF boosters used.

Again, it takes months and months to develop a sunscreen formula. You can get very different final SPFs from the same percentages of active ingredients. That means you can’t confidently say that a label is lying or not based on just those percentages. You also can’t confidently compare it with other sunscreens on the market, especially if they’re using different filters.

There are always new SPF boosting technologies coming out on the market and I’m not that knowledgeable about sunscreens, but here are two that I do know a bit about:

SunSpheres are a range of transparent hollow spheres and they can be made of a lot of different materials. These bounce UV around in the sunscreen layer so you get a longer path length – that means that the UV is more likely to hit a sunscreen molecule and get absorbed before it gets to your skin. It basically has the effect of making the sunscreen layer thicker.

Hallbrite BHB or butyloctyl salicylate is a solvent that can increase photostability and help spread out filters. The manufacturer has data showing that swapping this in for another solvent more than doubled the SPF of a zinc oxide sunscreen.

The DSM Sunscreen Optimizer actually has a function where you can put in different solvents and you can see what effect that has on the protection, but unfortunately this is currently broken.

So these are all examples of inactive ingredients that can drastically change the SPF of a sunscreen.

Comparing sunscreens from different markets

Another related point was that since larger Western international brands didn’t have sunscreens with lighter textures and lower percentages of actives, Asian sunscreens had to be lying.

The problem with this idea is that Western sunscreen brands haven’t really been aiming for this sort of formula. There just aren’t that many sunscreen nerds in Western countries that wear sunscreen every day.

The vast majority of people in Western countries only wear sunscreen when they go to the beach in summer and their skin gets really easily burnt. So the average western consumer expects to go into a supermarket and buy a sunscreen and not get burnt – even if they don’t apply enough, if they don’t reapply if they stay out in the sun for hours and hours and hours, if they brush against sand and towels and sweat a lot. Western brands tend to formulate for this type of usage and so their sunscreens often go well beyond what’s claimed on the label.

I actually got to talk to some of the top people in Neutrogena’s sun R&D team about their sunscreen development process. Neutrogena’s Helioplex sunscreens have to keep over 85% of their UVA protection after five hours of exposure to a midday sun lamp. If it’s 84%, they just won’t release it. They also test the wear of their sunscreens under all sorts of conditions, including extreme heat and extreme cold.

I’ve been told that some of La Roche-Posay sunscreens have well in excess of their labelled SPF protection. The highest allowed in Australia is SPF 50+, but they go well beyond this.

It’s only been in the last few years that some lighter textured sunscreens have been released). Even then the Hydro Boost still has that Helioplex label – probably so when a typical Western consumer grabs it, wears it to the beach and stays in the sun for hours, they don’t sue them because they got burnt.

On the other hand in many parts of Asia, daily sunscreen wear is very normal. That’s why there’s been a lot more effort into developing sunscreens that are as light and comfortable as possible, and generally that means cutting down the amount of filters.

But these sunscreens are often designed for day-to-day use – something like going to and from the office, and sitting indoors for most of the day. A lot of these sunscreens probably wear off quite quickly if you use them in a way that’s not expected – like a long sunny walk – and I think this is why some people have been getting burnt, even though they’ve been applying enough. It’s not really made for that sort of usage.

The properties of the sunscreen film make a big difference, and generally heavier sunscreens don’t move around as much.

In vitro SPF testing

So if we can’t tell what’s going on from just the active ingredients, what if we take the whole formula and test it with a machine?

The problem is human skin. You apply the sunscreen and the sunscreen interacts with your skin, and then your skin and the sunscreen film go out and interact with UV. So you still haven’t taken into account the whole equation.

The way that seems to work the best is by making special plates that mimic human skin, so when the sunscreen applies it dries on it just like it would on skin.

This sounds really obvious and straightforward, but it’s really not – scientists have been working on this for literally decades, and it looks like there’s finally a few methods that might be good enough to be accepted for SPF labelling.

The best method so far seems to be the Cosmetics Europe method. Very briefly, this uses a robotic arm (attractively named the Spreadmaster) to spread the sunscreen on two different specially roughened plates. They take four different UV absorbance readings, then they put it all into an equation that calculates the SPF.

This method is being rolled out and hopefully will be accepted in the next few years, but right now it still hasn’t gotten that official tick of approval.

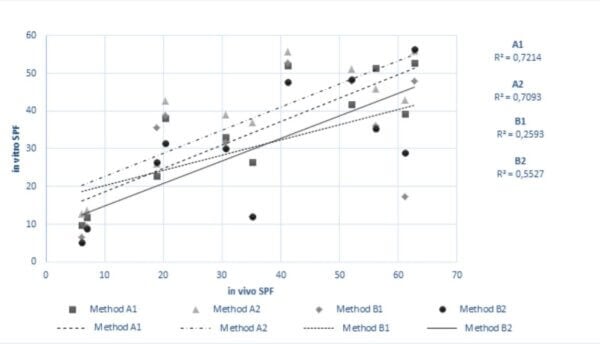

With other in vitro methods that use plates, there’s been a really big difference between what you see on the plate and what you see in vivo on human skin.

This graph shows the correlation for some methods and the closer the dot is to that diagonal line, the more accurate it is:

You can see some data points that are really far out here.

The two dots on the bottom right correspond to one that tested at SPF 35.1 in vivo on skin, but SPF 12 in vitro on the plate, and another that tested at SPF 61.2 on skin and 29 in vitro.

It also goes the other way – one sunscreen tested in vivo on skin at SPF 20.3, but all four in vitro methods overestimated it at SPF 31.5 to 42.7.

UV cameras?

Clearly testing in a lab without human skin can be really inaccurate – what if we test on human skin but with a simpler method?

One method I’ve seen suggested for checking how much SPF you have is by looking through a UV camera and seeing how dark it is.

I’ve actually spoken to the maker of one of the most popular UV cameras, the Sunscreenr, and he says that no, you cannot tell the SPF from how dark it is, as the camera is qualitative and not quantitative.

It only tells you where you spread the sunscreen, and possibly whether it’s gotten lighter or darker with the same sunscreen. But you can’t compare between different sunscreens – the darkness can’t tell you if it’s SPF 15 or SPF 100.

Part of this is because you can’t see how continuous the film is microscopically – it’s far too low resolution for that.

It’s also to do with how these cameras work. They use specific UV wavelengths, not the entire spectrum of erythemal UV (which is what’s used for SPF). If you have a sunscreen that happens to be really biased towards protecting against that particular UV wavelength, then it’ll be really dark. If you have one that’s particularly not biased towards that wavelength, it might be really light. But overall, the two sunscreens could end up working around the same.

Sunscreens that reflect or scatter UV also look a lot lighter, even if they’re only reflecting or scattering a tiny amount.

So the main thing you can tell with these cameras is just if you’ve missed a spot while applying – which is exactly what these cameras were designed for.

In Vivo SPF Testing

So all of these issues with these other methods is why the in vivo SPF test is still the gold standard. This is what’s used for the label. So unless you have evidence that matches up to the in vivo test that’s used for the label, you can’t really say very much and we can see that other tests just don’t really measure up.

But there are some issues with this gold standard, even though it is the best thing we have.

The main test used is the ISO 24444 SPF test – this was where you get human volunteers and burn them for science, and as mentioned before there are lots of issues with this like cost and harm.

But there is another really big reason why we’re so desperate to replace this test with an in vitro SPF test. It’s not very reproducible – in other words, testing the same sunscreen using this method doesn’t necessarily give you consistent results.

The differences between the SPFs that different labs get has always been a really big issue.

Testing bias

For example, Procter & Gamble sent the same SPF 100 sunscreen to five different labs. They told the labs that the SPF was somewhere between 20 and 100, and they got back five very different results between 37 and 75.

In another test, the five labs were sent another sunscreen and they were told that it was SPF 80. Three labs scored a pretty close to SPF 80. The two other labs gave at 54 and 70.

So when the labs were told in SPF value, they were more likely to get that expected result and so it looks like there’s some element of bias happening.

One thing I did notice in the INCI Decoder test was that the lab was told that the SPF would be around 20. I’m guessing when Purito did their test they told their lab that it would be higher, so this extra information might have influenced the results.

General methodology issues

There are a lot of other tiny, seemingly inconsequential things that can influence the results, which is why there’s been a revision to the ISO 24444 in 2019. Some of the things that are now specified which could give more accurate SPF results include:

- The sunscreen has to be applied in drops (at least 15 drops per 30 square centimeters)

- The drops have to be spread circularly and then up and down and then side to side

- The process of spreading the sunscreen on the skin has to be 30 to 40 seconds

- Through the whole process the gloved finger shouldn’t leave the skin

- The people who decide if the skin is burnt or not have to have their colour vision checked (it’s recommended that they get rechecked every year)

- Instead of having an expert classify the skin colour, this is measured by a machine; there’s a limit on the specific skin colours of volunteers and the average has to be within a certain limit

- The lamps that are used in UV testing shine a circle of UV onto the skin – they have to give out the same amount of UV a consistent amount over the area of the circle

So you can see there are a lot of things in the SPF test that could influence the result that weren’t actually specified before.

There’s also some things that still aren’t standardised and maybe can’t be standardised. For example, the person spreading the sunscreen is meant to use a light pressure. But one person’s light might not be another person’s light, and it’s pretty much impossible for the person to use the exact same pressure for every single sample they’re

spreading.

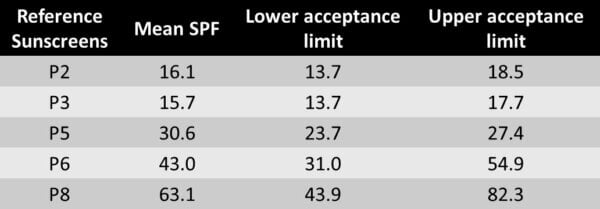

There are a few reference sunscreens used for SPF testing, and the labs use these to see how well that test was performed for that particular batch of people. The acceptable variation for each sunscreen is here:

You can see that as you get to higher SPFs, the accepted variation gets a lot bigger.

It’s actually a lot harder to measure a higher SPF. With these you can see that the upper limit is somewhere around double the lower limit – and remember this is considered good reproducibility.

Reproducibility between countries

The in vivo tests are pretty much the same around the world, but one factor that does change is the types of volunteers used.

In the ISO test you’re meant to use a range of different skin types from phototype I to III. This is now measured using a machine and skin color, but obviously depending on the country you’re going to get different volunteers coming in for these tests.

If you look at SPF testing data, you’ll often see this reflected. In Asian countries, you tend to get a lot more phototype III, and in Western countries you get a lot more phototype II. The test procedures are slightly different depending on how prone to burning you are, and so this could influence the final results.

This is particularly a problem if the tester gets the skin type wrong, and this is one of the things that machine measurement is meant to help fix. So SPF test results from different countries could be affected by this difference.

Batch variations

Along with the issues with the SPF test, there might be differences between different batches of sunscreen.

Sunscreen manufacturers usually get the label test on an early version of the sunscreen, and they might not re-test it with a proper in vivo test for many years.

Small changes in the production of the sunscreen can also affect the SPF value. There’s usually some testing for consistent composition – for example, to make sure there’s actually 5% avobenzone every time – but again, there are lots of other things in the formula that can change that SPF.

Sunscreens also settle over time, so depending on how fresh the sunscreen is, that can change the SPF as well.

Why two in vivo SPF tests?

So with all of these issues with in vivo SPF testing, that’s why I really think you do need two in vivo SPF tests to raise significant doubt over an SPF label claim. That’s what Judit says in the INCI Decoder blog post as well – if we only have one, then it’s really hard to say whether it’s just an issue with inter-lab reproducibility, or if there’s actually a problem with the sunscreen.

I think when you have two in vivo SPF tests that agree and one that doesn’t, that’s when you can confidently say there probably is a problem somewhere, and the burden of proof switches.

Purito posted an update saying they paused the sales of their sunscreen, and because people had complained to them about getting burned, they had actually sent their sunscreens off for extra testing earlier (the results hadn’t come back yet), which I think is the right thing to do.

There is still the possibility that the sample sent to the European labs was a particularly bad batch, or that the sample sent for the original testing in the Korean lab was a particularly good batch. The samples for the INCI Decoder test were also put into a different plastic container and then sent off for testing, so there is a possibility there that the sunscreen reacted with the container. Someone did point out that it says yellow whereas the Purito sunscreen is actually closer to white. It’s really subjective what colour a sunscreen is, but that could potentially be a sign of an issue.

Are Asian sunscreens dodgy?

Are Asian sunscreens less trustworthy? Since the Purito news came out, there’s been a lot of talk of not trusting Korean or Asian regulation or testing or brands, and only trusting larger Western manufacturers.

But sunscreens getting tested at SPFs that are lower than their labels has happened a lot of times before. There are a number of consumer advocacy groups around the world who retest sunscreens using in vivo methods, and a lot of the time they get results that are lower than the label. This happens with Western brands, including a lot of larger Western brands who put a lot of effort into making really good sunscreens.

It’s worth noting that the methods used in these consumer tests and in the INCI Decoder test aren’t quite the same as the label test. The biggest difference is the number of volunteers – for an SPF result that goes on the label, the results have to be consistent over at least 10 volunteers. In the consumer tests they usually just test on 5 or 10 people and don’t talk about consistency.

In one of the INCI Decoder tests they only use five results, and both tests weren’t consistent enough to be used on an SPF label. But these tests are in vivo and they largely use the same procedures, so I don’t think that affects their ability to raise doubt over an SPF label claim.

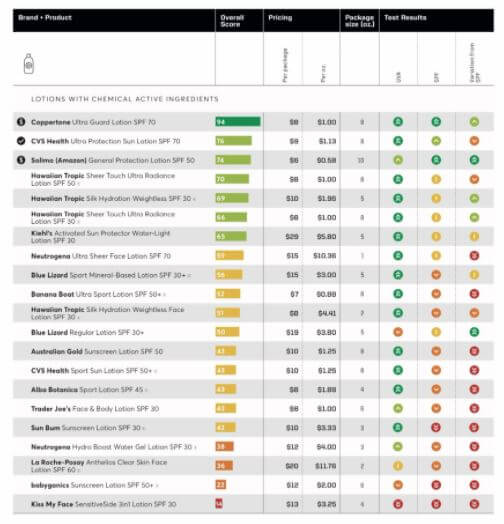

Consumer Reports in the US have found that a Neutrogena sunscreen and a La Roche-Posay sunscreen both tested at less than half their labeled SPFs. The Neutrogena one was labeled at SPF 70 but was tested at SPF 30-39. The La Roche-Posay one was labeled SPF 60 but tested at between 10 and 19.

In 2016, Consumer Reports found that 23 out of the 60 sunscreens they tested tested at less than half their labelled SPF.

In October this year, the Hong Kong Consumer Council found that 25 out of 30 sunscreens they tested had less than their SPF label. Some of the ones that failed include really large reputable sunscreen brands: Estée Lauder, iPSA, Anessa, Shiseido, Curél, Sofina, Laneige, Dermacept, Bio-Essence.

One thing that could be contributing to why it looks like there’s a higher fail rate for Asian sunscreens is that the consumer tests were conducted in an Australian lab. So that ethnicity difference could be an issue.

The worst performing sunscreen was one from Fancl, a Japanese brand. It was labeled SPF 50+ but it tested at SPF 14.3. The brand claims that the original label claim was supported by two tests from two different labs in two countries, US and China.

I would say that as a brand, the best way of checking the validity of your SPF rating is to send it to two different labs into different countries. But even though Fancl did that, there was still that discrepancy with the consumer test.

So in this whole Purito conversation some people have recommended that Australian sunscreens are the way to go. I’m Australian and I’m very proud of how my small country is going in terms of sunscreen regulation and development and skin cancer research – but this still isn’t error-proof.

In late 2015, Choice magazine tested six SPF 50+ sunscreens that were available in Australia, and they found that only two of the sunscreens in the consumer tests actually met the label claim.

European sunscreens have had SPF issues as well – there was a famous case with ISDIN, and 15% of sunscreens tested fell short of their label claim in consumer tests.

So this isn’t only an issue that you see in Korean sunscreens or Asian sunscreens.

The fact that this happened with Neutrogena and La Roche-Posay I think, isn’t a sign that these brands can’t be trusted or that any sunscreen that tests below the label claim must be lying. These are two western brands that I consider to be two of the most trustworthy brands in sun protection, and they always go above and beyond to develop high protection sunscreens.

Instead, I think it’s a reflection of issues with SPF testing and with batch variations and, in my opinion, a reflection of the robustness of some sunscreens – how consistently they perform over time in different conditions, which isn’t really captured by the current way of SPF testing.

(Note: The US Consumer Reports tests seem to use only water resistant sunscreens and test the water resistance SPF rating (similar to what’s required for the SPF label for any water resistant sunscreen), which includes an additional water soak test. The other consumer tests I looked at for this video (HK, Australian NZ) seem to have done a straightforward SPF test from what I can gather – the tests sometimes aren’t described in a lot of detail outside of the paywall.)

Fraud happens

On top of this there’s the fact that, at the end of the day, you are still relying on people to do the right thing.

The biggest sunscreen labelling scandal that’s ever happened is with AMA Labs, one of the biggest US-based sunscreen testing labs.

According to the indictment, the lab committed fraud over 30 years between 1987 and 2017. They allegedly conducted SPF testing on far fewer people than they said they did, sent in fraudulent results and pocketed the extra difference.

One of the sunscreen brands that got caught in this AMA Labs mess was Sunsense. I consider them to be one of the best sunscreen brands in Australia, and they publish a lot of peer-reviewed research and collaborate with dermatologists continuously. In consumer tests, Sunsense sunscreens have fallen short – the AMA Labs test could be to blame.

This also happened with another really reputable brand, New Zealand’s Cancer Society. So again, it happens to brands that are super trustworthy by any measure.

These issues can apply to the Purito test or the INCI Decoder test. Were they both really the Purito sunscreen? Did INCI Decoder accidentally get a fake tube? Did someone somewhere along the line accidentally use the wrong sunscreen? Like AMA Labs (allegedly) did someone just completely make up the numbers? It’s really hard to be sure without any extra testing.

I don’t think there’s necessarily any wrongdoing on anyone’s part here – there are explanations that don’t involve that. My gut feeling is that it’s more likely than not there is some sort of issue with the sunscreen, and that can range from whether it’s just really not that robust or someone has straight up being fraudulent. It’s impossible to say where in the process this has happened and whose fault it is.

From the actions that Purito have taken (particularly the fact that they’ve been releasing lots of information that they’re not legally required to) I’m leaning towards there not being any intentional wrongdoing on their part. For now I’m personally treating the Purito sunscreen as an everyday sunscreen that doesn’t necessarily have higher than SPF 19.

What the hell do I do?

If you’re new to all this information, I know it can feel really daunting – you might be wondering how you can trust any sunscreen brand ever again.

But please don’t freak out! Keep in mind that there are people out there who have known all these issues with SPF testing, and all of these consumer reports for years and years, and they still use sunscreen.

So at the end of the day with all of this uncertainty, how can we be somewhat sure that we’re picking a sunscreen with good protection?

Unless you’re testing every tube of sunscreen that you use on a panel of people, there is no way to be absolutely sure that the rating you’re getting is the rating on the label – just like you can never guarantee that your frozen berries don’t have hepatitis A, and that your car doesn’t have lethal airbags.

But if you do want to go beyond the SPF label, here are some of the things that point towards a more reliable sunscreen despite all of this uncertainty:

- An SPF that’s validated by an International Consumer Research and Testing (ICRT) report

- A water resistance rating

- A higher total concentration of sunscreen filters

- The presence of known SPF boosters and film formers in the inactive ingredients

- A thicker product consistency (e.g. sticks are better than lotions)

- Getting a sunscreen from a country that regulates sunscreens as drugs or functional cosmetics (and regulates them pretty well)

- A brand that is large enough to attract the attention of regulatory authorities

- Good storage conditions and purchasing from a reputable retailer

There are a lot of things in my suggested list that aren’t compatible with each other ,or aren’t compatible with your life, so there’s going to have to be some compromise.

Sunscreen sticks tend to give the best protection, provided you apply enough. But consumer groups tend not to test sticks, and sticks tend to be really uncomfortable and clog your pores.

US sunscreens have been tested the most by consumer groups, but US sunscreens have lots of problems. They use the older filters that aren’t as stable in the sun, they have a lower requirement for broad spectrum, and the filters tend to be more allergenic and irritating.

European sunscreens tend to use the newer filters, tend to use higher concentrations and have thicker textures. But they’re regulated as regular cosmetics, not drugs.

Australia has the newer filters, a good broad spectrum rating system and sunscreens are regulated as drugs. But if you insist on having validated SPFs, then you’re kind of out of luck because there’s only ever been six that have been tested, and only two of them passed. Plus, this was back in 2015 – both of these sunscreens have been relisted since, so their formulations might have changed.

If you have to buy a sunscreen from overseas, then you can’t be certain about the conditions that it goes under on its way to you.

It’s always best to go for a sunscreen that’s suited for what you’re doing. For example, if you’re just staying mostly indoors then you probably don’t need to care about as many of this criteria. If you’re spending a long time in the sun, then you want something that ticks off more boxes.

If you’re using a sunscreen and you’re getting burnt, or your pigment is getting darker, then it’s a sign that the sunscreen isn’t working for you. Whether it’s mislabeled, or not water resistant enough, or you’re just not managing to apply enough – whatever the reason is, it’s time to switch to a different sunscreen.

And it’s important to remember that sunscreen is not a suit of armour, and it’s only one part of sun protection. Wearing a hat, wearing sun-protective clothing, seeking shade and avoiding the sun in the middle of the day are super important.

One thing I find helpful when I’m worrying too much about sunscreen – whether my sunscreen is reliable, whether I’m using it correctly – is remembering the results of the Nambour study.

This was the biggest study ever on sunscreen involving 1600 people. One group put sunscreen on every day on their head, neck, hands and arms, and the other group just used sunscreen when they felt like it.

After 4.5 years, the skin of daily sunscreen users had no detectable increase in aging, and they were 24% less likely to show increased signs of aging. Invasive melanomas were almost four times less common in daily sunscreen users.

These results are even more incredible because the study was done in the 90s, using a 90s sunscreen that was SPF 16 with 8% octinoxate and 2% avobenzone. And this was done in Queensland in Australia, where there’s a LOT of UV. So even if your sunscreen application isn’t optimal, you are still getting a lot of protection.

I hope you enjoyed this deep dive into some of the issues around SPF. This only really just skims the surface, but hopefully the complexity of the whole situation makes a lot more sense now!

References

Racz J, Purito Centella Unscented Sun tests as SPF 19 in two different European labs, INCI Decoder, 3 Dec 2020.

Consumer Reports, Consumer Reports finds that nearly half of sunscreens tested did not meet their SPF claims, 17 May 2016.

Reddit /r/skincareaddiction, Consumer Reports 2020 sunscreen ratings, 25 May 2020.

Bray K, SPF 50+ Sunscreens put to the test, Choice Magazine, updated 13 Feb 2018.

Consumer (NZ), 5 more sunscreens fail to meet SPF claims, 30 Jan 2019.

Consumer Council (HK), Over 80% of sunscreen performed below their labelled efficacy increase the risks of skin darkening, sunburn or even skin cancer, 15 Oct 2020.

Magramo K, Industry backlash against Hong Kong Consumer Council study which finds 83 per cent of sunscreen products do not meet protective claims, South China Morning Post, 15 Oct 2020.

Euroconsumers, The sunscreen scandal: Euroconsumers meets with the Commission, 17 Feb 2020.

Staton J, Changes to ISO Sunscreen Standards, seminar for IFSCC, 10 Jun 2020.

Osterwalder U, Uhlig S, Colson B, Vollhardt J, Good as gold: validating alternative SPF test methods, Cosmetics & Toiletries, 3 Apr 2020.

Dimitrovska Cvetkovska A, Manfredini S, Ziosi P et al., Factors affecting SPF in vitro measurement and correlation with in vivo results, Int J Cosmet Sci 2017, 39, 310-319. DOI: 10.1111/ics.12377

Pissavini M, Tricaud C, Wiener G et al., Validation of an in vitro sun protection factor (SPF) method in blinded ring‐testing, Int J Cosmet Sci 2018, 40, 263-268. DOI: 10.1111/ics.12459

Department of Justice, Owner of AMA, a rockland based consumer products testing company, arrested for fraud scheme involving fabricated test results, 9 Aug 2019.

Sunscreen testing company boss arrested for defrauding clients, Cosmetics Business, 15 Aug 2019.

Foxon-Hill A, An honest mistake: when zinc based sunscreens go wrong, Realize Beauty, 9 Aug 2015.

BASF Taiwan, The development trends of sunscreen products in China, 2020.

Thank you so much for taking the time to explain this so thoroughly and clearly. I am a skincare enthusiast and I have learned so much from following you on Instagram and reading your articles. I was a big fan of the Purito sunscreen and was disheartened to hear about what happened, but you have given me a much better framework for how to evaluate sunscreens moving forward.

I wish that this was found out a month ago! I only used Purito on weekdays during work and used a sports sunscreen when exercising. Last month I was gardening and used Purito because the weather was cool and I wasn’t going to be very active and sweaty. I was fried! I was confused because I had on a hat and was only outside for 30 minutes.

Thank you for so much rigor in your information!

Thank you for such a balanced and in depth article. I found it most interesting

Thank you Michelle!

My personal experience is, however, that the “Centella Green Level Unscented Sun is not even a SPF 19. My guess would be SPF 5 or 10.

I have always used a SPF 50 on my face and neck and have no tan lines. This summer I switched my regular spf for the “Centella Green Level Unscented Sun”.

After 2 days of 1 hour of sun, I had visible tan lines on my neck and stopped using it immediately.

Thanks.

Your article was so helpful!, as well as thought provoking. One of my questions continues to be, what if the Purito brand sunscreen has regularly worked well for me?, which is the case. I don’t understand how people can have such different experiences with one product, unless as you mention different batches, working differently. Looking forward to the results! And thank you again Michelle!

Last summer I had been using a couple of sunscreens depending on what I was doing and how long I expected to be outside. After about a week I noticed that I was getting “colour” in my face. I could press my finger against my skin and it looked white and between my scalp and face there was a difference in colour. (I always wear a hat and avoid direct sun all the time!) I was alarmed. I stopped using the Klairs sunscreen which had been one of my absolutely favourites (sadly!) and switched to Annessa waterproof by Seishiedo (sp?) and my colour after a week returned to normal. So your advice to use waterproof is so true! And I was caught by surprise with Klairs.

I have struggled in wearing SPF daily because most break me out. My possibly too pragmatic outlook is: even if the Purito or Klairs sunscreen are *lower* than advertised (both of which I have, ironically), it is probably better for me to wear SPF 19 daily than SPF not at all.

Thanks for another terrific and informative article. I love the Klairs product however as a California resident I now am concerned it may not have enough coverage for when I take a walk at lunch – and I have 3 tubes of it left.

Any recommendations for boosting it’s spf without adding a layer of another brand sunscreen? Powder suncreen? spf foundation?

I experienced the same result a few months ago when I purchased and used Purito Sunscreen after reading your review. I always use a high SPF sunscreen when outside, another brand. Admittedly, I was gardening on a sunny day for several hours, applying Purito several times, thinking my very red face was do to the outside temperature. It was not. I ended up with a very red, swollen face, most severely under my eyes, even though I wore a hat and dark sunglasses the whole time. Needless to say, I stopped using it after my severe reaction.

Thank you for this article, I now know the reason for the reaction.

As mentioned, the people wearing sunscreen on a daily basis aren’t doing so for health reasons, but instead for vanity. And where vanity is concerned, UVA protection should be paramount.

With all the social media outrage directed at Purito’s false SPF claims, it’s as though the people being outraged are focused on the wrong thing. They should instead be clamoring for regulation / standardization on measuring UVA.

I am curious how protecting one’s skin from long-term sun damage and potential skin cancer is a vanity decision? If the choice is vanity (skin color) – can be achieved or at least aided by cosmetics, the effort of daily sunscreen plus additional protections seems to be a lot more effort.

I don’t disagree with the idea of championing better testing, just the assumptions you’ve made on the daily sunscreen wearer.

I couldn’t agree more. I didn’t wear sunscreen for vanity reasons ever. I started wearing sun block 35 years ago on the advice of my aunt who is a (now retired of course) ER nurse who also had a sun allergy. When exposed to any sun at all she would break out in rashes. In my late ’30’s (I’m now 66) a dermatologist that was seeing for an unrelated issue told me there is ONLY ONE decent anti-aging cream which is super inexpensive that he knows of, and that’s sunscreen. That reinforced what my aunt had advised years earlier. I don’t believe people generally use sunscreen for VANITY – they use it to protect themselves from sun damage including cancer which is a very real threat (and one that’s growing exponentially yearly with our decline in the ozone). People who don’t take sun block seriously are playing roulette with their health. I thank my younger self DAILY for having used sunblock faithfully for more than 35 years. My skin glows with great health and vitality to show for it! I respect Purito however for its incredibly responsible response to these sad test results. It has inspired me to trust this company more than ever on all their products and when they re-release a sunblock in the future I’ll be the first in line to buy it!

Let’s be serious.

The loudest voices of outrage on the Purito scandal are on r/skincareaddiction and other r/(fill in the blanks). If you’ve read most of the posts there, you’d know very well these aren’t people much worried about skin cancer. It’s about vanity in addition to the rest of their 27-step skin care routines.

Somehow, our parents and grandparents managed to live without skin cancer just fine without slathering on sunscreen on a daily basis. In fact, incidental sun exposure from going about your day isn’t likely to contribute to skin cancer. The cancer is driven by genetics and the cumulative impact of careless behavior (and in Australia’s case, the unfortunate depletion of ozone).

Really? My grandfather had melanoma on his ears and nose thanks to an outdoor job (park ranger) and no sunscreen. Skin cancer existed back then, my dude.

Yes you’re so right Emily! I knew people back in the ’70’s who had skin cancer. The problem however is that the threat is much greater. When I started using sun screen (early ’80’s) I was using a 15 SPF while out in the sun all day in Mexico! I came home as white as if I hadn’t been south at all – no one believed me honestly 🙂 now a 15 would be problematic. In fact I had been using the Klairs and did notice some colour in my face which I found alarming. I don’t believe we should be using anything less than 30 and that’s on dark, winter, overcast days at most. Most days in the summer I wouldn’t venture out less than a 50 PA++++.

My MIL had 2 melanomas removed off her legs. It’s quite sad to see people now in their 50’s and older who are constantly having atypical moles removed. A lot of men particularly get lesions on their face and upper back. Back in the 80’s there was the “slip, slop, slap” marketing for skin protection but many people only felt the need to apply sunscreen if they were going to the beach for the day or attending a sports game. Not the incidental exposure.

what about the purito comfy water? Should we assume there is the same issue.. if there is an issue?

Thank you so much for this post! I have chosen to use sunscreens that are approved where I am (The FDA is pretty thorough) instead of foreign products aren’t approved here. And thank goodness for that I guess. I used Purito before, but I just got tired of always having to order abroad. I’m not knocking Asian products, but I just feel better about sticking with products that are regulated here. I like L’oreal’s Memoryxl. This post really helps to understand this whole thing in great depth. There’s no perfect answer. Though I won’t lie I am very disappointed that I wasn’t getting the protection that I thought I was back when I was using Purito! I’m just going to not think about it though because there’s nothing I can do about it now! 😬

Thank you for the thorough post Michelle.

Since Klairs sunscreen uses the same filters and has a similar texture…should this be a cause of concern?

It seems to be made by the same lab, which is a bigger cause for concern IMO.

Hi, I live in the US and I’d really like to get a sunscreen with tinosorb or a more advanced filter than mineral sunscreens for broad spectrum due to living on the west coast. I’ve tried to get the Ulta Violette and La Roche Posay sun cream, but they aren’t shipping those to the US. It looks like the only one I can find with tinosorb is the skinceuticals one, but it’s also so expensive. Do you have any recommended alternatives?

Thank you for this! This being said, do you have some sunscreens you do recommmend?

This was amazing, Michelle. I’m surprised sunscreen formulators don’t all eventually lose their minds. Mine is currently spinning with the insane number of tricky areas in the development process. Two things I kept thinking: 1) finding the right sunscreen seems to be as tricky as finding the right person; you just have to keep trying. And two: If tricky things about making sunscreen were a drinking game, every player would die of alcohol poisoning.

Hi Michelle, did you see RatzillaCosme’s post on 3rd-party sunscreen testings in Asia? https://www.ratzillacosme.com/updates/2021/06/third-party-sunscreen-testings-some-thoughts/

She covers some interesting discrepancies for East/South East Asian consumer tests.

I think she has a good point with how Asian brands tend to produce different sunscreens with the same name, which leads to confusion for consumers (and IMO it erodes their reputation – I’m very disappointed that Shiseido does this) – it would be great if they didn’t do that! But I disagree with many of the points:

* The Consumer Reports test replicates the official water resistance test used in many places (US, Australia, EU, Brazil etc.), so it isn’t a “made-up methodology” or “terrible science” – perhaps she’s less familiar with it because there’s no regulation for water resistance in Japan. Third party tests from ICRT organisations usually use valid methodologies (but with lower reliability due to sample sizes).

* In vivo UVA testing is not considered by sunscreen scientists to be superior to in vitro UVA testing – in vitro UVA tests are standardised by comparison to in vivo SPF results for the same sunscreen, and there isn’t a universally recognised biological endpoint for UVA like erythema for UVB.

* She didn’t mention this in this particular post, but I’ve seen her say elsewhere that the Consumer HK tests that found some Japanese sunscreens were invalid because they used in vitro tests, but they used in vivo (https://twitter.com/ratzillacosme/status/1340471948535447552)

Dear Michelle

I am so grateful for the time you take to go through all the research , lay it all out so beautifully in an objective and unbiased way and then explain it so thoroughly to us. This is so incredibly valuable on many levels, including teaching people how to question what they are told and how to assess data. You are amazing and truly providing an incredible public service. Bless you. Thank you for sharing all your energy and expertise