You’ve probably seen hundreds of these sorts of videos and infographics giving you lists of foods to stop eating to cure your acne.

Is there any truth to this? Are all these foods actually giving us acne? Here’s a deep dive into the science behind food and acne.

A quick warning: I’ve had a lot of requests for this topic, but obviously diet talk can be very harmful, so if you’re trying to avoid talk of diet and food, this might not be a good post for you. Lots of dermatologists like my friend Dr Anjali Mahto have seen some of the damage that diet-based skincare advice can cause – she’ll be giving some practical advice a bit later. But you’ve probably heard about the diet and acne studies, so let’s talk about them.

The video version is here on YouTube, with all of my terrible dancing.

Food impacts skin

Firstly, there is zero doubt that things you eat can potentially impact your skin. We get basically every chemical our body needs from food (apart from things like… oxygen) and skin is part of our bodies.

But a lot happens in between putting food into your mouth, and substances from the food affecting your skin.

- Your digestive system breaks down the food into its individual chemicals

- Some of that gets absorbed into your blood

- Your liver and kidneys filter the chemicals and transform some of them

- A whole bunch get yeeted out of your body

- Some of the substances that end up in your blood get taken up into your skin (about as far from your blood as your body parts can get), or they might influence one thing in a long pathway that ends up affecting skin

And a lot of other things can impact steps in this process: stress, sleep, hormones, genetics, skincare products, your microbiome, medications.

On top of that, we know there are tons of other things that impact acne. Acne is a very complex condition, so it’s very possible that everything else has a much larger impact that you can’t overcome with tweaks to your diet.

So “you are what you eat” is technically true, but it’s not as straightforward as it sounds. It’s incredibly tricky to work out how specific foods in someone’s diet might impact that specific person’s skin.

Can you even trust the science?

Science to the rescue! Let’s do some controlled experiments and see what happens!

But it turns out – studying how diet impacts skin is just straight up annoying.

In a scientific experiment, we ideally want to change one thing at a time for a proper test. That way, you can be somewhat confident that the thing you changed (the independent variable) caused the effect you saw (the dependent variable).So let’s say we wanted to work out if chocolate caused acne.

The perfect study would look something like this…

Large group, diverse subjects: We would get a good mix of people – a few thousand to make sure any effect we saw wasn’t a fluke.

Control (comparison) group: You would make them eat and do everything the same, except you’d give half of them chocolate, so you could compare what happens with and without chocolate.

Double blinding: You’d also want to make sure no one knows if they’re eating chocolate or not. This is because of expectation bias – if someone knew they were eating chocolate and they expected to get more pimples, maybe they’d subtly change their other habits, or they’d be stressed about it, and that could affect the outcome.

Same with whoever’s assessing the skin and counting people’s pimples (double blinding). Maybe if they expected people eating chocolate to have more pimples, they might count a borderline bump on someone in the chocolate group as a pimple.

Control all other variables: The two groups would use the same skincare products, have the exact same diet, the same foods from the same brands apart from the chocolate, they’d eat the food at the same time, they’d drink the same amount and types of alcohol, they wouldn’t be allowed to smoke, they’d sleep the same amount, have the same amount of stress, the same exposure to sun and pollution.

You’d want to keep the people in specialised accommodation so they can’t go off and have secret midnight snacks.

Long study time: You’d also want to run the study for a good amount of time, because of hormones and stress. For example, you’d want there to be enough cycles that you have a good idea of whether it’s the chocolate or hormones causing any acne, so probably at least… 6 months?

Anyway, it turns out you’re not allowed to jail people for 6 months for science even if you pay them, and you have to pay people a lot to convince them to let you control every aspect of their lives.

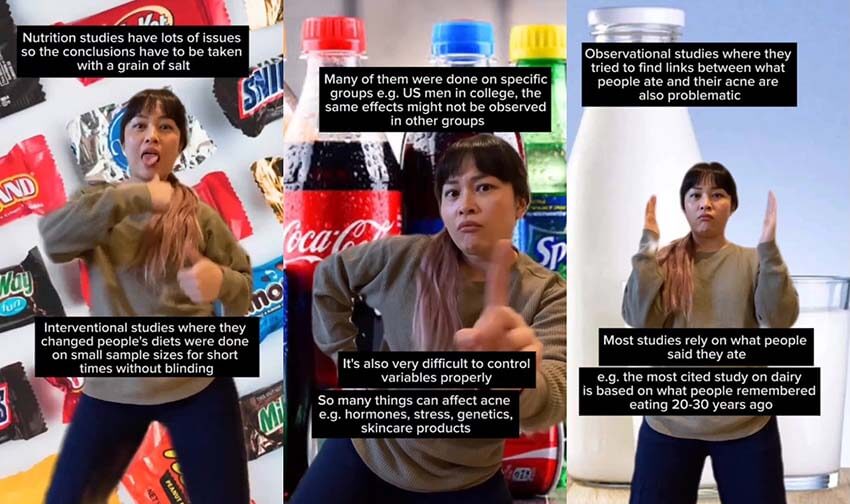

So this perfect setup never happens. Nutrition studies have to make a lot of compromises, so it’s a lot harder to be confident in the results.

And because the studies aren’t really controlling all the variables, a lot of other things (confounders) can affect the results. So unsurprisingly, a lot of these studies have contradictory results.

Keeping in mind what our perfect setup looks like, let’s have a look at the two types of studies on food and acne that we actually get.

INTERVENTIONAL STUDIES

The first type are interventional studies, where scientists change people’s diets and see what happens.

This sounds a bit like our ideal situation, except:

Sample size: These studies usually have less than 100 people. Often a lot less – we’re talking an average of thirty-something people in the trial, which means about 10-20 people in each group, e.g. 17 people getting chocolate and 17 not. That’s… not a lot.

It’s difficult to be confident that there wasn’t a fluke involved. For example, it’s quite possible that two people in the chocolate group just happened to have honking big pimples that week for some other reason, like it’s exam week, or it’s a particular point in their menstrual cycle.

Controlling variables: Another issue with these studies is that they usually don’t tightly control what the participants eat. Chocolate studies usually give people a specific type and amount of chocolate to eat (which introduces a blinding problem – it’s hard to hide what food people are eating!), but they don’t tell them what else they should be eating. So, maybe having the chocolate meant they didn’t feel like eating as much fruit or ice cream, and it’s actually lack of fruit or ice cream that’s causing less pimples.

Diversity of subjects: A lot of these studies are also on very specific groups of people – for example, there are a lot of studies where all participants are male 20-something college students in the US. Most studies purposely use men because the studies don’t go for very long, 4 weeks or less, and with women there’s the menstrual cycle which has a massive effect on acne. (The college students part is because it’s very easy to bribe college students into doing a study.)

So this very limited group of people studied means it’s difficult to see whether the results would also apply to a woman in her mid-thirties like me, or a teenage girl, or a male college student in Japan. We know that genetics can have a big role in how people process food, e.g. lactose intolerance varies across ethnicities and by country.

So generalising these studies, which happens all the time on social media, is a big problem. You’ll see the results of these studies turn into an image on a cute infographic, or 3 seconds in a TikTok video, but there’s none of this extra context – 3 of the 4 small studies on chocolate published in the last 11 years were done on just male college students.

And there just aren’t a lot of interventional studies on diet and acne. A 2021 review looked at all the studies in the last 11 years, and they found… 11 interventional studies. That’s 11 studies, not on chocolate and acne – 11 interventional studies on ANY dietary change and acne since 2009.

Like I said, good dietary studies are expensive and complicated to run, even though these are very far from our ideal situation, even with all these compromises, they’re already rare.

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

There is another type of study that adds to what we know about diet and acne: observational studies. These look at what people are already doing, and try to find patterns. For example, do people who eat a certain type of food tend to have more acne?

There are more of these studies because they’re less of a pain to run, and they tend to have a lot more participants and more diverse participants.

But they have a lot of other issues because the participants are just going about their everyday lives as the scientists record what they eat and how their skin is going.

Controlling variables: Firstly, there’s a massive amount of variation in what people are eating and doing during the study. There are a lot of little things that could be impacting the results that won’t be recorded (stress, sleep, hormones, skincare products etc.)

Data quality: Secondly, there’s an issue with recording what people ate and what happened to their skin. In observational studies, participants usually have to tell the scientists what they ate.

Now, if you know you have to record your food, it might change what you eat, and you might self-edit your food diary a bit. And if you’ve ever had to record your food intake for whatever reason, you know how hard it is to record every single thing you eat. And it’s impossible to work out how much of each ingredient you’re eating if you eat at a restaurant or get takeaway. I recently had some random food allergies I haven’t figured out yet, and the number of times I’ve told myself I’ll write it down later and then just straight up forgot is ridiculous.

A lot of the time, the studies don’t get people to record their food, but they get them to fill out a survey about what they ate – the obvious problem here is if it’s hard enough to accurately remember what you ate today, it’s really really difficult to remember what you ate over the last two weeks. Some of these diet and acne studies had participants try to remember what they ate years ago! The most highly cited study on dairy and acne got their data by asking women in their 30s and 40s what they ate when they were teenagers.

These issues make it harder to draw strong conclusions about what food caused what effect with observational studies.

Let’s have a look at a recent observational study (the NutriNet-Santé study) as an example:

The scientists got 24 452 people (75% female) in France to track what they ate over 3 days at the start, middle and end of a year. The participants were also asked whether or not they had acne.

They found a statistically significant association between current acne and consumption of fatty and sugary foods, sugary beverages and milk.

So at face value, it seems like this study is saying that eating more sugar leads to more acne, but if we take a closer look…

Sample size: We have lots of people, which is good!

Data quality: The study used surveys for recording food, which has the usual issues with imperfect recall and self-editing.

There’s also the fact that most people don’t eat the same thing consistently over a week, let alone a year, so that three day snapshot might not reflect their usual diet.

Then there’s the other data point – the acne. Out of the people who said they had acne, 44% diagnosed themselves. Only 37% were diagnosed by a dermatologist, and even dermatologists can get it wrong. So it’s quite possible they didn’t actually have acne, it could be something that looks similar like folliculitis or rosacea.

Confounders: There are also a lot of other factors that might be messing up the results.

Three-quarters of the subjects were female, which means there are a lot of hormonal factors that might skew the results. For example, PCOS affects somewhere around 10% of women of reproductive age and is strongly linked to acne. Hormonal contraceptives can increase or decrease acne – roughly half of women in France use hormonal contraceptives.

Eating more sugary foods might also lead to people eating less of other things – vegetables, fruit – and it might be having less of those that led to the acne, and not the sugary food.

Eating more sugary foods may also be a reflection of something else. People who eat less sugary foods might be more health-conscious in the rest of their lives, for example: they might have a closer relationship with their doctor, they might exercise more, or they might have a less stressful lifestyle. Correlation isn’t causation.

The association they found between acne and fatty and sugary foods, sugary beverages and milk is also quite weak, which means that it’s difficult to say if there would still be this association if we took out some of these extra factors.

WHAT DOES THE EVIDENCE SAY?

With this background, you can hopefully appreciate how hard it is to confidently say much about links between diet and acne. And that’s why dermatology organisations are so careful with their recommendations when it comes to diet and acne.

The strongest links we have with the rather flawed evidence are pretty weak associations, which means it’s hard to say that eating these foods actually caused the acne, and that stopping these foods will stop the acne for a particular person. But the 2 things there are the most evidence for so far are:

High GI/GL diets: These diets have lots of refined sugar and carbohydrates that absorb quickly into your bloodstream, and they seem to be the strongest link there is between diet and acne.

It’s still a weak link – for example, of the three interventional studies on low GI/GL diets and acne, two of them found a relationship but one of them found no significant difference in acne with high vs low GI diets.

Some dairy products: High intake of dairy products seems to be associated with acne. This is a particularly confusing one because dairy is a really broad category and different studies define it in different ways.

It seems like low fat and skimmed milk are more strongly linked to acne than full fat dairy. Yoghurt and cheese don’t seem to be linked. Whey protein might be a problem.

With both high GI diets and dairy, the proposed ways that they could be leading to acne are similar: both of them can increase the levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and insulin in blood. Increased IGF-1 can increase androgen hormones, specifically the “male” hormones testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). These can increase the production of sebum, the natural oil in your skin that can clog your pores. Increased sebum is one of the contributors to acne.

Higher IGF-1 also leads to overgrowth of keratinocyte cells in your skin, which could contribute to clogged pores as well. Both diets could also lead to inflammation, which could also contribute to acne.

Unfortunately, all of this extra context doesn’t make for a great viral TikTok video.

HOW DO WE USE THIS INFORMATION?

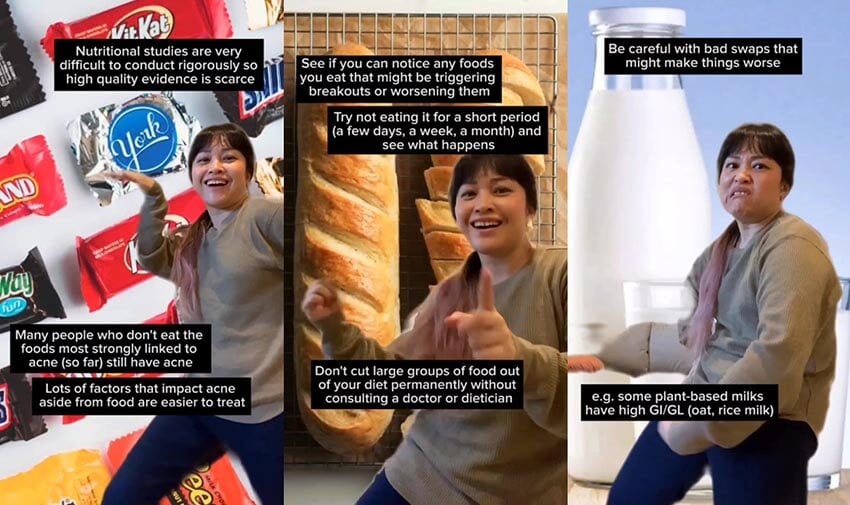

So the science on the link between food and acne is really not all that solid – which isn’t that different from a lot of things in skincare, where there’s a lot of grey areas.

But the difference between skincare and food is that adding or removing a skincare product generally isn’t a big deal.

Changing your diet is a much bigger deal, especially when it comes to the two types of food we have the most evidence for. Dietary changes can affect a lot more than just your skin. High GI foods and dairy are in lots of common foods, so being very black and white, and restricting yourself to a fraction of the foods you used to eat can easily lead to nutritional deficiencies and a wildly unbalanced diet.

And more importantly, it can have a massive impact on your mental health as well – in particular, with disordered eating.

For example, you’ve probably heard of orthorexia, which is essentially an unhealthy obsession with eating the “correct” foods.

One of the first published case studies on orthorexia was a woman whose orthorexia started when she was told to cut out fats to try to control her acne.

There are lots of other examples in the literature and around the internet, where trying to cure acne with dietary changes have started an eating disorder, or made it worse. It’s not uncommon on skincare forums to see people talking about what foods they can’t eat, how hard it is to avoid these foods, how they’re avoiding going out with their friends to control temptation, how much guilt they’re feeling when they eat one piece of the “wrong” food.

So with all of this in mind – all the issues with the evidence, the potential dangers – you want to be very cautious when messing around with your diet to try to clear your skin.

Dr Anjali Mahto: “The evidence is not robust enough at this moment in time to recommend dietary changes alone for the management of acne.”

The official recommendation is to see if you can notice any foods you eat that might be triggering breakouts or making them worse, then try not eating it for a short period and see what happens.

If you do want to change your diet to see if it impacts your skin, here are three tips from Dr Anjali Mahto.

Tip 1: Be careful with bad swaps that might make things worse

Anjali: “There are a small select group of people that may be sensitive to dairy. So if you do want to cut dairy out of your diet and you want to switch to a plant-based alternative, maybe rather than jumping from dairy to oat milk – which is a common swap that I see people making – think about unsweetened soy or almond milk instead. The reason for that is oat milk has actually got a very high glycemic index.”

Tip 2: Switch out whey protein

If you drink whey protein shakes, see if you can use a different protein source.

Anjali: “I think that’s one situation where people may benefit again from switching to a plant-based protein instead – particularly because the amount of cow’s milk protein that you effectively get in a whey protein supplement is actually quite significantly high. We’re not talking about a little splash in your coffee or a little bit in your porridge.”

Tip 3: Consider bringing in an expert

Anjali: “If you are genuinely thinking of removing things from your diet, you should really do it in conjunction with a professional dietitian. If you start removing lots of things, you may end up with essentially a diet that is missing a lot of important nutrients that you might need for your overall general health – which is obviously a situation that we want to avoid.”

And be really careful with taking and spreading simplified dietary advice – there can be very real harms involved.

Anjali: “I see a lot of patients that will cut out huge food groups – and usually it is dairy, gluten, and sugar.”

“If you look hard enough, if you cut those three things out -according to the internet – you can fix every skin condition.”

“…and it gets to the point where their skin’s not getting any better, they’re getting really anxious about the foods that they can and can’t eat. And what ends up then happening is people find themselves in a situation where their diet becomes more and more restrictive, there is more anxiety around food, and almost the development of disordered eating patterns because you become so paranoid that anything that you might eat might trigger your acne.”

So if diet isn’t a great way to try to fix your acne, what might be a better idea?

Anjali: “I think if you are going to try and manage your acne at home before you seek professional help, I think actually looking at your skin care routine is a far better starting point than starting to cut things out of your diet.”

“Now if you have changed your skincare up, you’ve been doing it for a good four to six weeks, but you’re still finding that your acne is not getting any better, or it’s getting worse, or it’s becoming more extensive – so it’s not just affecting the face but it’s extending onto the neck, the back, the chest, the shoulders – if it’s starting to scar or leave permanent markings (and about 20% of people who have acne will get permanent scarring), or if it’s starting to affect your mental health, it’s affecting your day-to-day and your confidence – all of those then are signs that you should then move on to professional help. You’ve done what you can at home, and you’ve given that a good bash.”

And unfortunately this makes for an even worse viral TikTok video.

(I put all of Anjali’s insights on food and acne here on my secondary channel, if you want to find out more! Her Instagram (@anjalimahto) is also worth a follow – her posts are always very insightful and balanced. Her website is here.)

Selected References

American Academy of Dermatology, Can the right diet get rid of acne?

British Association of Dermatologists, Patient Information Leaflet: Acne, last updated July 2020.

Dall’Oglio F, Nasca MR, Fiorentini F, Micali G, Diet and acne: review of the evidence from 2009 to 2020, Int J Dermatol. 2021, 60, 672-685. DOI: 10.1111/ijd.15390

Baldwin H, Tan J, Effects of diet on acne and its response to treatment (open access), Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021, 22, 55-65. DOI: 10.1007/s40257-020-00542-y

Penso L, Touvier M, Deschasaux M, et al., Association between adult acne and dietary behaviors: findings from the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort study (open access), JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 854-862. DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1602

Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Holmes MD, High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne, J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005, 52, 207-214. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.007

Reynolds RC, Lee S, Choi JY, et al., Effect of the glycemic index of carbohydrates on acne vulgaris (open access), Nutrients 2010, 2, 1060-1072. DOI: 10.3390/nu2101060

Burris J, Shikany JM, Rietkerk W, Woolf K, A low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: a short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial, J Acad Nutr Diet 2018, 118, 1874-1885. DOI: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.02.009

Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, Jung JY, Park MS, Suh DH, Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial (open access), Acta Derm Venereol. 2012, 92, 241-246. DOI: 10.2340/00015555-1346

Ramezani Tehrani F, Behboudi-Gandevani S, Bidhendi Yarandi R, Saei Ghare Naz M, Carmina E, Prevalence of acne vulgaris among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systemic review and meta-analysis, Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 392-405. DOI: 10.1080/09513590.2020.1859474

Catalina Zamora ML, Bote Bonaechea B, García Sánchez F, Ríos Rial B, Orthorexia nervosa. A new eating behavior disorder? Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2005, 33, 66-68.

I am a huge fan of Dr. Anjali Mahto and I completely agree with you – stressing out about which foods to eat is probably worse for the skin than keeping your diet. There are many reasons to try eating less refined sugar, but the key is always balance and never black and white dogmas.

Wow!!! Thank you for going over this with such detail and clarity!!! I have rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia and have become increasingly skeptical about the many things recommended you eat or don’t eat and supplements you take or don’t take to relieve my symptoms. Over the 59 years I have had RA, I have tried so many natural remedies and eliminations and none have seemed to impact it, although have caused other issues, usually digestive. So your article not only helped my skin, it showed me that food studies are VERY difficult to do. Thank you!!!!!!!

I’d like to say something about how helpful and informative this is but I CANNOT GET PAST THE FACES YOURE MAKING IN THE FAKE TIKTOKS OH MY GOD IM HOWLING, NEVER CHANGE GIRL <3

Thank you for the great article Michelle! So many great things here that need to be said. Yes, the links between diet and acne are unclear- even with glycemic load, the total GL of what we eat is affected by other foods we are eating simultaneously making it very difficult to interpret!

Thanks for bringing up the harm that can be caused by following restrictive diets…especially without professional guidance.

I’m encouraged to see truth being spread by other professionals regarding nutrition. Keep at it!

-Avery, B.Sc. Human Nutritional Sciences, Graduate Dietitian