HBO has a new 4 part documentary Not So Pretty which talks about supposedly dangerous beauty products. This kind of documentary comes out every 6 months or so, and everyone panics and throws out their products.

Like pretty much everyone I think, I’m concerned about my health, but not so into people trying to exploit this concern for attention, or for profit. So I watched this documentary with some of my cosmetic chemist friends (Jen of The Eco Well, Stephen of Kind of Stephen, Esther @themelaninchemist and Lalita @skinchemy).

The video is here (including me attempting comedy), keep scrolling for the text version…

Episode 1 is called “Makeup”, and it’s mostly about asbestos in talc.

Talc is a powdery ingredient that’s commonly found in makeup and baby powder, and there’s some controversy about how talc can sometimes be contaminated with asbestos. Asbestos is a spiky mineral that’s linked to some forms of cancer.

The episode discusses what happened with Claire’s makeup, which was found to contain asbestos in 2017, and Johnson & Johnson Baby Powder, which is the subject of a whole bunch of lawsuits from plaintiffs claiming it caused their cancer – mostly ovarian cancer, but also mesothelioma, a cancer that’s closely linked to asbestos exposure.

Documentaries aren’t science

Before we go any further, I need to remind everyone: documentaries aren’t science.

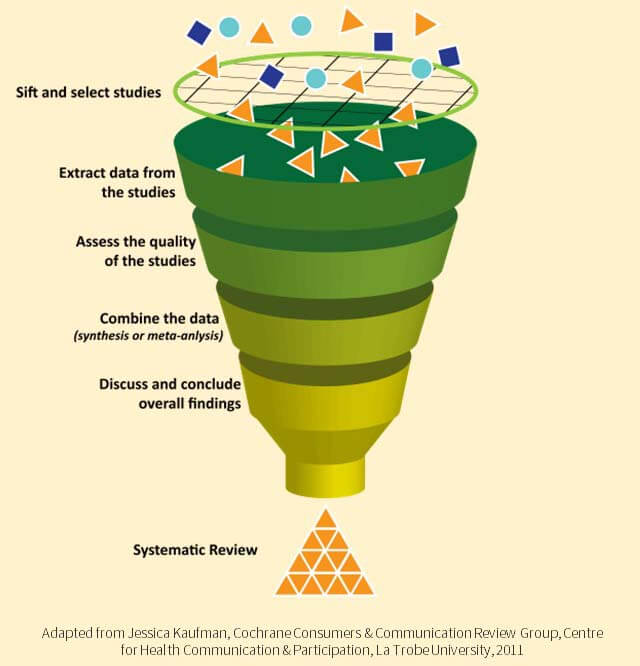

In science, we try to conduct fair tests, then look at all the data to work out what it tells us. If the studies disagree, you have to work out which studies are flukes, which ones weren’t fair, which ones aren’t relevant, and which ones were just plain wrong. If there’s no conclusive answer, you need to work out how much certainty there is, and what the sensible thing is to do in the meantime.

Documentaries don’t have to play by these rules. They need to tell a good story, and this story is chosen by the filmmakers who generally aren’t experts in the topic – they’re experts in making films.

You would hope that the documentary makers would consult relevant experts, and base their documentary on what the science says, but there’s no obligation to do that.

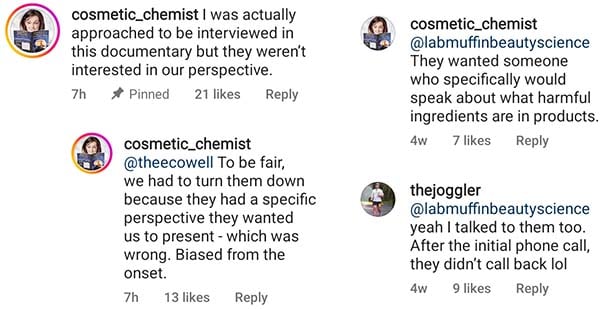

You’d also hope that they’d try to be transparent, that they’d say if the relevant experts they approached disagreed with what they said (foreshadowing).

But again, there’s no real rules. They can choose to only show the bits of evidence that fit the narrative they already had in mind – this is commonly called cherrypicking. It’s like only showing footage of snow, to make it seem like global warming isn’t real.

And unfortunately, science is complex. It usually doesn’t make as good a story as a sensational, black and white, cherrypicked narrative that plays on fears and misconceptions that we, the audience, already have.

And if I watched Not So Pretty without already knowing a lot of the background, I probably would’ve been quite convinced. This is a really slickly-made series that does actually bring up some good points… but it mixes them in with a lot of really bad points, that they support with very unobjectively selected evidence and questionable leaps of logic.

Not So Pretty Episode 1

The main theme of the first episode Makeup is the idea that most beauty products with talc contain asbestos, and therefore have a high chance of causing harm to consumers. They’re mostly talking about powder makeup (like eyeshadow and face powder) and talcum powder.

The episode focuses on a 26 year old woman, Corrin, who was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a type of cancer that’s usually caused by asbestos.

Palmer (narrator): After Corrin was diagnosed with mesothelioma, she decided to have the makeup products she owned that contained talc tested. 10 of her 25 makeup products contained asbestos.

Palmer (narrator): …the cases involving Kristi and Corrin clearly point to a concern with many other talc products.

So the documentary makes the case that the asbestos in Corrin’s makeup caused the mesothelioma, and that her story is representative of the dangers to consumers from talc in makeup. They also talk about how Kristi found asbestos in Claire’s makeup in 2017, which was a huge story at the time.

And this leads to the conclusion:

Corrin: …and it’s not gonna stop unless talc products are no longer being used.

To me, there are a lot of issues with this whole line of reasoning.

Asbestos is uncommon in makeup

The first issue: the documentary never mentions that there’s a lot more data on asbestos in talc products, other than this one woman’s makeup collection and what happened with this one brand. The reason that asbestos in Claire’s makeup was such a big story was that it was shocking – it’s rare and unexpected.

And quite glaringly, the documentary doesn’t talk about how this Claires incident actually spurred the FDA to start investigating asbestos and talc in cosmetics. There’s a section of the FDA website that’s entirely dedicated to talc.

This is a huge thing for them not to mention, to the point where it feels like they deliberately left it out – because the documentary does talk a lot about how the FDA doesn’t do enough.

But for this specific issue with talc and asbestos, the FDA have actually done something – they’ve been updating methods for detecting talc, and looking for asbestos in talc-containing products. They did two surveys in 2019 and 2021, and they used the more sensitive techniques that the geologist in the documentary mentioned.

I find it hard to believe that the documentary makers could’ve missed this – the page comes up immediately if you Google “talc FDA”.

- In the 2019 FDA survey, 52 products from 23 brands were tested. Asbestos was found in 9 products from 3 brands: 3 out of 5 products from Claire’s, 5 out of 7 products from City Color, and 1 out of 2 baby powders from Johnson & Johnson.

- In the 2021 survey, 50 products from 33 brands were tested, and no asbestos was detected in any of them.

So in total, that’s 3 brands out of 53 that had talc-containing products with asbestos, and 9 products out of the 102 tested that had asbestos. These are most likely higher than what’s on the market, because the FDA prioritised testing brands and products that they suspected had asbestos.

On the other hand, 10 out of 25 of Corrin’s products had asbestos. This is close to half, which doesn’t seem to be representative of talc-containing cosmetic products on the market overall.

Makeup use isn’t a risk factor for mesothelioma

There’s also the fact that people who use more makeup don’t seem to be noticeably more prone to mesothelioma.

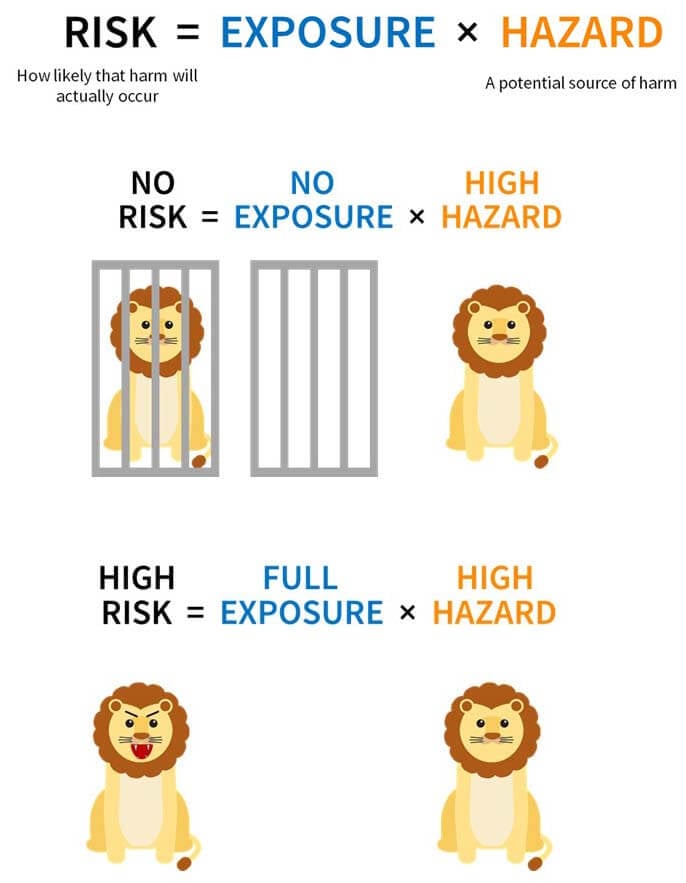

Mesothelioma is linked to asbestos exposure, but it’s usually prolonged, heavy exposure, such as in people who work in industries where there’s a lot of asbestos, and even then most asbestos workers don’t get mesothelioma. Asbestos is a trace contaminant in cosmetic talc, and as the FDA surveys showed, it’s not often in there. When it is, it’s in really tiny amounts.

On the other hand, before the mid-1980s, large amounts of asbestos were used in construction since it’s a good insulator and it’s fireproof. It was used in wall insulation, pipe insulation, roof shingles, textured ceilings and walls. Two thirds of houses built between the 1930s and 1980s in Australia contain asbestos, as do more than half of US homes.

It generally isn’t a big problem unless you’re renovating your house, or the panels containing asbestos are falling apart – because they’re getting old, or because of a natural disaster. This can release the spiky asbestos particles into the air and you can inhale it, which is the main route of exposure that leads to mesothelioma. There’s also asbestos in old brake pads, and as they wear down the asbestos fibres go into the air.

So typically, the people who get mesothelioma are blue collar workers who work closely with lots of asbestos as part of their job – asbestos miners, people who make products with asbestos, people who work with asbestos like construction workers and brake mechanics.

There are also higher rates in people who live near asbestos mines and factories, and people who live with asbestos workers, since they can bring home asbestos dust on their clothes. On top of that, asbestos in the air is high in a lot of cities because of brakes.

4 times as many men are diagnosed with mesothelioma than women, and most of these men are over 65, which overwhelmingly points towards working with large amounts of asbestos being the biggest issue. In the US, there are about 3000 diagnoses per year, so it’s a relatively rare cancer.

There’s no known increased risk for makeup artists, or people who manufacture cosmetics, or mothers with many children, which you would expect if using makeup or baby powder was a big risk factor. And the amounts of asbestos in makeup and baby powder are so small to begin with, compared to how much is in a lot of homes, for example.

This doesn’t mean that asbestos in makeup and baby powder will never cause even a single case of mesothelioma – you can be really unlucky, a tiny asbestos fibre could just happen to land in the exact wrong place to cause health problems. But more exposure to asbestos means there’s a higher chance of this happening.

And it seems like a pretty big distortion of the actual risks to spend 35 minutes talking about tiny amounts of asbestos in a small number of makeup and baby powder products, and warning people to avoid all products with talc, without ever mentioning how you should be careful about drilling into walls in older houses, or cracked ceiling panels, or getting an asbestos evaluation of your house before you renovate. All of these things could reduce your exposure to a lot more asbestos, and are recommended on official health websites, whereas avoiding makeup and baby powder usually isn’t.

And one possibility that Stephen raised in our live viewing is that, maybe it would be worth investigating if Corrin has an asbestos problem in her house?

Stephen: Do they ever test her home? I’m wondering if maybe her house was contaminated, and like things were … settling into the makeup…

Probability-wise, it’s a much more likely explanation for why a young woman might develop mesothelioma than using makeup, and it would also explain why her makeup products are so much more contaminated than the products on the market. Maybe they did investigate it, but it’s not mentioned.

Whether or not that’s the underlying reason, her experience isn’t representative of the overall safety of talc-containing products in the US.

Anecdotes like these are really persuasive – we can see these people, we relate to them, we get emotionally invested in their stories – but it’s still just one example that may or may not tell us about the overall picture and the real risks that we should be worrying about.

Related post: Science vs Anecdotal Evidence and Reviews (with video)

Not So Pretty’s Experts… and who they left out

The choice of experts that Not So Pretty used in this episode also seems to point to cherrypicking.

In this episode, they only feature one relevant scientist, a geologist (Sean Fitzgerald) who analyses talc samples for asbestos.

Almost all of the explanations we’re given about the science of asbestos and talc, and their health risks, are from two lawyers – both representing plaintiffs in talc cases – as well as a journalist. So it’s an extremely one-sided view that’s being presented – we are basically just hearing one side of a court case.

You would maybe expect some input from relevant, qualified scientists, like cosmetic chemists, or toxicologists working in cosmetic safety or asbestos. So why don’t they appear in this?

It turns out that some cosmetic chemists were actually approached by the documentary makers – Perry and Valerie of The Beauty Brains podcast – but their perspective didn’t match what the documentary makers seemed to already have in mind. They didn’t hear from them again. And I’m sure they couldn’t have been the only relevant experts they approached and left out.

Makeup isn’t baby powder, mesothelioma isn’t ovarian cancer

It’s also a bit questionable how this episode is called “Makeup”, and starts and ends talking about make-up, but most of the time is actually spent talking about baby powder.

I think this is because there is a stronger case against baby powder – there’s a lot more talc in baby powder than makeup to begin with, and most of the lawsuits on talc are against Johnson & Johnson.

So why did they focus so much on makeup rather than baby powder, and try to blend the two together?

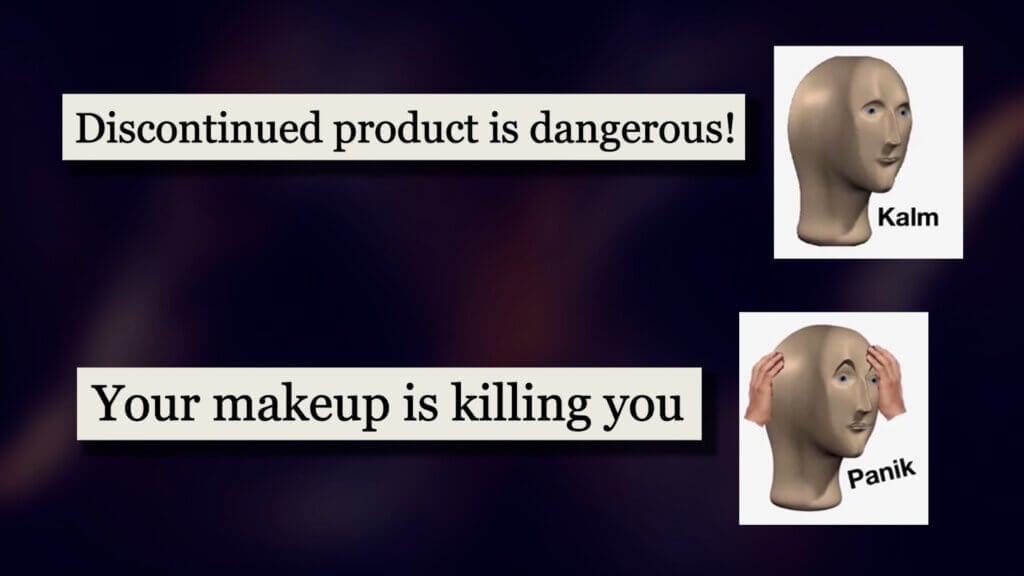

I would guess it’s because J&J actually stopped selling talc-based baby powder in the US in 2020, so a baby powder episode wouldn’t be as attention-grabbing. “This thing you probably don’t own and probably can’t buy anymore could be dangerous” is not going to be as viral as “The stuff you use every day could be dangerous”.

As Jen mentioned in our viewing, it’s also worth noting that most of the lawsuits were actually about talcum powder causing ovarian cancer and not mesothelioma.

Again, this seems to be a deliberate choice, because a paper looking at data from over a quarter million people was published in 2020. It found that there was no significant increase in the risk of ovarian cancer for people who used powder in their genital area. Notably, the authors weren’t involved in any talcum powder litigation cases, which is very rare for newer publications about talc.

So it seems like the documentary makers have purposely gone for a smaller issue that’s a bit harder to debunk, because the main issue’s fallen through.

Real issues, wrong solutions

All the episodes of Not So Pretty also bring up real, complex, important issues involving inequality, race, access to healthcare, workplace reform, and social justice.

But a lot of the time they imply that we can solve these problems just by changing the ingredients in your products.

For this episode, they say consumers can act by avoiding all talc products (which as discussed earlier, isn’t a recognised risk factor), and they didn’t mention any of the better recognised preventative steps you could take that medical organisations recommend.

They also recommend using:

Palmer (narrator): …apps like Skin Deep, Detox Me, and Clearya which rate and rank product safety and list dangerous ingredients.

So it’s really pushing clean beauty apps and clean beauty logic, where ingredients are neatly divided into good and bad, and you can work out how safe a product is based on the ingredient list. I’ve talked about it before – it’s a clever marketing technique, but it’s just not how the world works.

Related post: Clean Beauty Is Wrong and Won’t Give Us Safer Products

How safe an ingredient is depends on how you’re exposed to it. This is a very basic principle in toxicology.

The most important factor is how much there is – a concept that’s commonly referred to as “the dose makes the poison” – and the ingredient list doesn’t have any numbers.

Clean beauty apps and websites also often misinterpret studies. They’ll take studies on cells and animals, where they might’ve fed the ingredient to rats or injected it into them, and just assume they have the same health impacts in humans.

And proper trained toxicologists have actually analysed the same studies before and published their conclusions, and cosmetic chemists use ingredients in products based on these recommendations.

So on one side you have scientists with years and years of specialised knowledge saying that these ingredients are safe when used in certain ways, and the formulators who know where they get their ingredients from, know the impurities in the raw ingredients, know how much they put in the product, know these safe recommendations.

And then on the other side you have these clean beauty organisations that don’t know how much is in the product or where the ingredient comes from saying it’s unsafe, plus these organisations seem not to know humans aren’t cells in a petri dish or rats, and just the basics of toxicology.

The two sides are really not equal!

And then to recommend clean beauty as the solution to these complex social problems – it makes me really frustrated, because these issues really need to be solved, and the well-researched solutions are complex and a lot of people are working on them. But Not So Pretty are really emphasising these oversimplified, fake solutions that aren’t supported by the evidence, so they won’t solve these issues and could just act as a distraction and make things worse.

And a lot of the ways this episode brings up these issues in the first place just don’t really make sense. For example, one of the lawyers said:

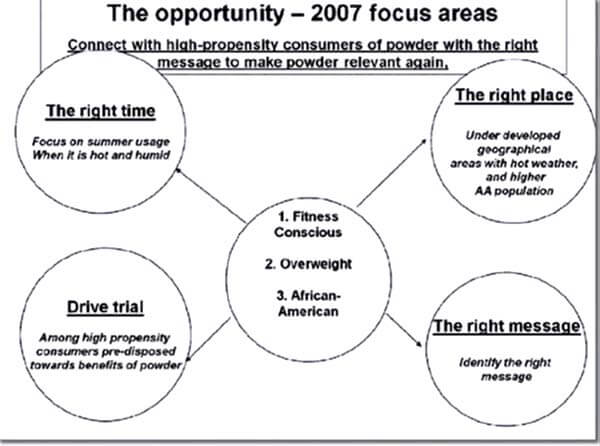

Iola: [J&J’s baby powder marketing] targeted African American women that were overweight that lived in the South.

This is made out by the documentary to be kind of sinister and predatory, and that “according to lawsuits”, it had something to do with the fact that this demographic would be less likely to get an early diagnosis. And again, inequality of access to healthcare due to race and other socioeconomic factors is a big problem.

But demographic-based marketing is standard – people from different cultural backgrounds use different products. And one of the big uses of baby powder is for reducing chafing between the thighs in hot sweaty weather. So it seems like there’s a much more straightforward explanation that doesn’t involve a huge evil conspiracy.

The documentary also says that J&J:

Flint: …are still making the product in South Africa, in Colombia, and in India, so they’re really targeting women of color with a product that could be carcinogenic.

But J&J’s talc baby powder is also still sold in a whole bunch of very white European countries, like Ireland, Switzerland, Germany and Norway – which goes against the “targeting women of colour” theory.

The Good Points

The good points I think this episode made:

Not enough resources for cosmetic regulation

Chaudry: There is really no government authority that is checking to see whether the products are actually safe.

I would love to see governments devote more resources to checking product safety, and enforcing the regulations that already exist to protect consumers.

I think a lot of us have seen posts on social media about products with mould growing in them, product textures changing in worrying ways, products with dishonest advertising like filters and illegal drug claims. Some of us have even submitted complaints to regulators and have realised that very little of these get dealt with in any official sort of way.

This isn’t just an issue in the US – it’s a problem pretty much everywhere, and the FDA actually does more than a lot of other countries. The EU system tends to get recommended by a lot of clean beauty advocates, but for this specific issue, their regulators haven’t explicitly investigated asbestos in cosmetic talc, or published any surveillance testing like the FDA studies.

I think it’s a bit of a crap situation that a regular consumer had to send the Claire’s eyeshadows off for testing before the asbestos was discovered. It just seems like the sort of issue that regulators should be more proactive in tackling.

Legal loopholes exploited by big corporations suck

I also agree that the Texas two-step scheme that J&J are using sounds pretty crappy. It’s a legal loophole that allows companies to massively reduce payouts in lawsuits. But it seems unsurprisingly that companies are going to try to reduce their losses as much as legally possible – hopefully legislation closes this loophole soon.

Takeaways

Firstly, asbestos doesn’t seem to be a common contaminant in cosmetic talc, according to better evidence that seemed to be purposely ignored in the documentary.

If you’re still uncomfortable using talc, maybe avoid using talcum powder. This is one of the bigger sources of talc, and cornstarch-based alternatives work pretty well. The amount of talc per makeup application you’d inhale is pretty small to begin with, and based on the FDA surveys, asbestos in makeup doesn’t seem to be a big issue.

More importantly, if you’re worried about asbestos, be aware of more significant contributors to your asbestos exposure, like your home and any other buildings you regularly go to. Check out official health websites for more information on asbestos.

When watching documentaries, be vigilant about the ways they might be manipulating you. Some things are hard to spot without knowing the topic already, but in a lot of documentaries, one obvious red flag is the experts they use. Ask yourself:

- What experts are they using?

- Are they the right experts for the topic they’re discussing?

- Are there obvious categories of experts missing? If so, look up what these experts are saying.

I’ll be talking about the other episodes soon – stay tuned for that!

The full conversation from our watch party is a podcast on The Eco Well, if you want to hear more about what we thought.

There’s also a great book by Geoffrey Kabat called Getting Risk Right which I highly recommend if you want to get your head around how to avoid getting on the panic carousel with these sorts of issues.

References

Center. Talc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/talc

O’Brien KMTworoger SSHarris HR, et al. Association of Powder Use in the Genital Area With Risk of Ovarian Cancer. JAMA. 2020;323(1):49–59. DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.20079

This is a great article. I really appreciate your work.

Thank you!

Thank you for breaking this down in such an entertaining way. Yes, we still get the baby powder here in Germany but as someone living in a house build 1914 my main source of exposure for the longest time was probably our garage roof we had replaced two yers ago…

Excellent as usual.

It takes a lot of work to write these analyses.

Thanks a million.

I just downloaded the Yuka app which told me almost all my cosmetics were carcinogenic, so immediately went to the Lab Muffin to get the facts. You never disappoint! Looking forward to your whole series on these. 🙂

This is so refreshing to have someone with a background in chemistry examining these problems and demonstrating how fear mongers use these issues to scare people, solicit donations, and increase their following. We need a lot more science educators like you to counter the epidemic of self-serving misinformation.