More beauty brands are talking about sustainability, but there’s a lot of greenwashing.

In the last installment we talked about the impact of producing natural ingredients and after they go into the environment, as well as organic versus conventional farming.

In this part, Jen of The Eco Well and I are breaking down myths about synthetic ingredients made from petroleum (petrochemicals) and plastic packaging – and talking about how to actually be sustainable.

The video is here, keep scrolling for the text version…

Myth: Making synthetic ingredients from petrochemicals is worse for the environment

There’s this idea that synthetic ingredients made from petroleum are bad for the environment, because petroleum is a fossil fuel.

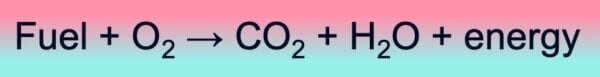

Yes, fossil fuels are bad for the environment. Extracting petroleum through processes like fracking can be very destructive. And there’s also all the carbon dioxide that gets released when they’re burned as a fuel, to release energy, which is the main driver of climate change.

But there are some big differences between petroleum as a fuel and ingredients that are made from petroleum.

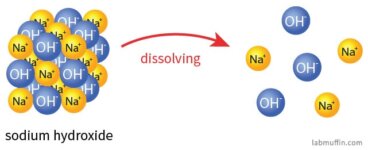

Jen: There’s no petroleum sourcing with the intent of making cosmetic ingredients. The petrochemicals that are used are all waste products from the petroleum sector.

Societally, we want to move away from our reliance on fossil fuels. But until the world does, and while the world is fuelled by them, the byproducts that cosmetics use will be there. In the future, this may not be the case, but this is the current reality.

And making natural ingredients also consumes fossil fuels. Tilling, making fertiliser and pesticides, moving water for irrigation, harvesting, transporting plant materials, processing, purification – all of this uses energy, which usually comes from fossil fuels.

And this time, the fossil fuels ARE purposely dug up and burned as a source of energy. And that burning is the part that releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

If petroleum jelly isn’t burnt, the carbon stays sequestered in the petroleum jelly and won’t directly contribute to climate change.

Again, it depends on the specific situation – synthetic isn’t always less impactful than natural.

Making synthetic ingredients, processing and purifying them also uses energy, and this again mostly comes from burning fossil fuels.

And again, some natural ingredients are also made from waste materials from other processes, which means energy savings and less carbon dioxide.

Related post: Are Natural Ingredients Better for the Environment?

So it all comes back to looking at the data for each individual ingredient, which means life cycle analyses. A few examples:

Jen: An LCA from Symrise show(s) that their synthetically produced menthol produced eight kilograms of CO2 per kilogram menthol, versus 50 to 100 for its natural counterpart.

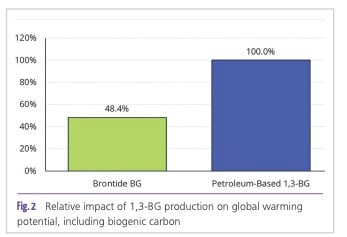

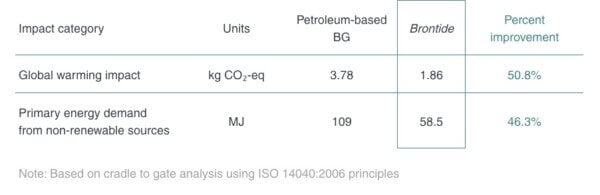

In contrast, Genomatica’s Brontide butylene glycol – they halved their CO2 emissions with the use of plant-based starting points via biotechnology, instead of the traditional production from fossil fuels.

Then again, since they use a genetically modified biocatalyst in this process, many consumers and eco certifiers still view this as unsustainable.

There is no blanket rule about natural always being more sustainable. And when we’re considering whether or not natural materials are more or less impactful, we should be asking:

Are we using prime agricultural land to produce them, or are they coming from waste or byproducts from crops that we’re already using anyway in other sectors?

This also means there’s no blanket rule about what benefits the fossil fuel industry more: buying synthetic ingredients made from petrochemicals, or buying natural ingredients that use a lot of fossil fuels to produce.

And speaking of myths about petrochemicals, we need to talk about packaging.

Myth: Plastic is bad

The idea that plastic is always worse than other types of packaging is everywhere – not just in cosmetics – and it is, again, a massive oversimplification.

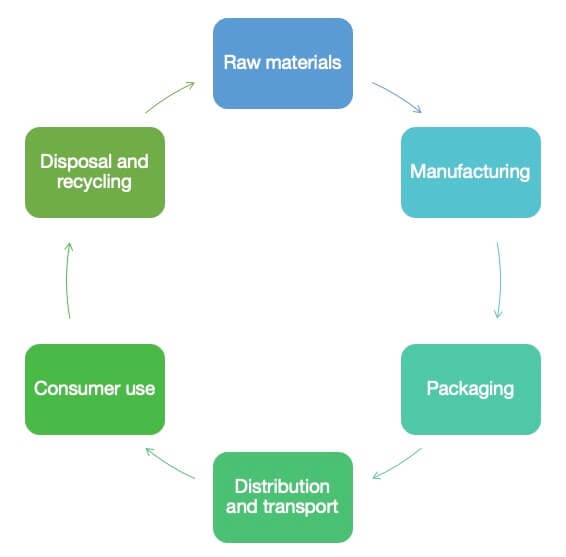

Like I mentioned before, a lot of this is because we tend to focus on just the end-of-life part when we buy products, because we have to personally deal with it. Does the bottle go to landfill, or can it be reused or recycled? Does it degrade?

And just like before, end-of-life is just one part of environmental impact.

Jen: If we stop using all plastic and use more “eco-friendly” alternatives instead, like glass, paper and aluminum, we would need on average 3.6 times the material, 2.2 times the energy, and an average increase of about 2.7 times the carbon dioxide emissions.

This makes a lot of sense if we look at each part of the life cycle, plastic isn’t universally the worst option for any part.

For example, with production, plastic is produced via byproducts of the petroleum sector. Contrast that to paper, where there’s a lot of processing from wood. And then glass and aluminum – they can come from recycled sources, but there is a lot of heat involved that increases the impact.

One of the things we need to remember is why plastic packaging became so widespread in the first place. It’s really good at protecting the stuff inside it.

Jen: To transportation. For example, with glass vs plastic. Plastic is lightweight for its strength, and therefore the transportation CO2 emissions tend to be less.

There’s also the matter of glass breakage. And similar for aluminum – aluminum is heavier, it dents easily, and people don’t want to buy it then.

Even for end of life, mono material plastic can be recycled about 40 times.

And some companies, to strive for eco options, are switching to partly paper packaging, which ends up needing a plastic layer since paper doesn’t stand up to, for example, water. And then as a result, they end up using multi-layered materials that are harder to recycle and ends up being worse.

Ultimately here, the best packaging option in terms of the environmental impact is a case by case basis with the best option varying greatly from individual formulations and users.

For example, what are the user’s habits? What kind of recycling infrastructure do they have available? Is your bottle return program something that they can viably access?

Blanket statements that plastic equals bad are both, from my perspective, unhelpful and potentially harmful.

At the end of the day, there’s no silver bullet for sustainable packaging, and every option has its pros and cons.

What can we do?

So hopefully from all of this, it’s clear that sustainability is complicated, and straightforward blanket rules don’t work. We can’t just always choose natural or organic products, or choose glass over plastic, and expect that we’re making the better choice.

So what can we actually do to be more sustainable?

Less consumption

I think the most obvious thing to do is to just consume less. Buying something is almost always going to be less sustainable than NOT buying something, regardless of whether it’s “eco-friendly”.

Jen: Per capita, consumerism is the most environmentally destructive thing we do societally. The overwhelming evidence shows that the negative impacts associated with over consumption vastly outweigh any of the positives associated with “green” innovation.

So it’s important to consider if you really need to buy something – because a lot of companies make it seem like you’re saving the planet just by buying their product, when in reality, it’s probably going to have a net negative impact.

And this is filtering into regulation – for example, the UK CMA has already said that labels like “green”, “sustainable” and “eco-friendly” could be considered deceptive unless a business can prove that as a whole, there’s a positive environmental impact to using the product, which is pretty unlikely.

Jen: “There’s a push towards green consumerism, which is ultimately at odds with sustainability as it paradoxically increases consumption, which increases impact.

Also there is a market incentivization for “green”. Consumers are willing to pay more for products they perceive to be green, and there is also a rapidly growing market for impact or ESG investment, where investors want to invest in companies they, again, perceive to be socially or ecologically superior.”

Ask questions

Given how complex sustainability is, I think it’s also important to ask questions. If a brand says their product is sustainable, ask them for evidence.

Because there’s so much complexity, we can’t work out what’s going on without brands providing some level of transparency. We don’t know how the butylene glycol in their product was made, or whether their production plant uses renewable energy.

Jen: Companies pursuing sustainable development must have access to as much relevant information as they can, to make the best possible decision. They must measure and record data in terms of their specific goals.

Environmental accounting is the backbone of sustainable development – you can’t be accountable unless you’re actually accounting for things.

Life cycle assessments can be seen as the most important tool for understanding a product’s impact. Actually calculating specific environmental impacts of every single ingredient and how much is going into the product, or how things are being transported, etc.

A lot of the time, the clean movement just bases their ideologies on assumptions, like assuming that natural is always safer.

If we want to move to reduce our impacts, we need substantiation and we need the specific measures to be relevant and standardized so you can actually make comparisons between companies.

Most of the current popular “eco” standards, certifiers and labels you see around don’t do this very well.

And as a consequence, they may actually be resulting in more greenwashing rather than true sustainability progress despite how they’re positioning themselves.

Be more informed

It’s also important as consumers to be informed about what things are actually more sustainable. The beauty industry responds to consumer demand.

If we push for the wrong thing – for example, non-evidence-based eco certifications, or less plastic, or more natural ingredients, regardless of what the environmental impacts are compared to alternatives – brands will deliver it, so we might be contributing to making everything worse.

Like we saw with clean beauty, people pushing for paraben-free products meant that brands started using less effective and more irritating preservatives that led to more skin reactions, maybe an “allergy epidemic”, and products that go off faster.

Related Post: Clean Beauty Is Wrong and Won’t Give Us Safer Products

So it’s important not to go for easy answers, and make sure you’re sharing the correct information. And if you see people and brands spreading myths, it’s important to counteract that and tell people where they can find better information.

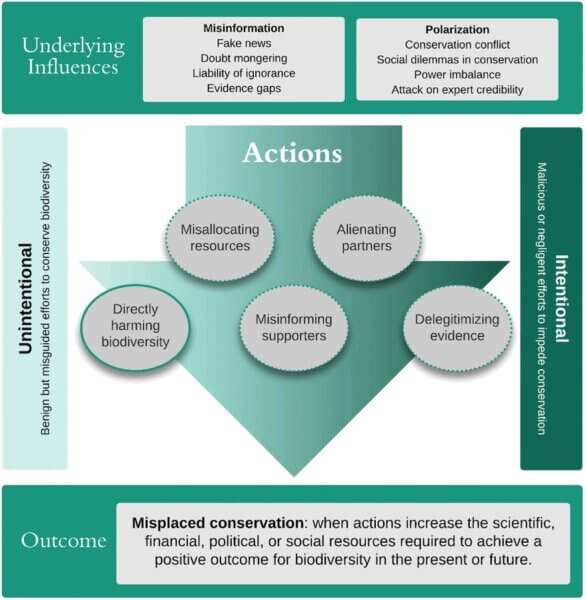

Jen: A problem we’re increasingly seeing is misplaced conservation, where misinformation and polarization can actually work together against sustainable development.

For example, by leading to a misallocation of resources into efforts that fundamentally don’t make sense – sometimes making the issues that they’re trying to address worse.

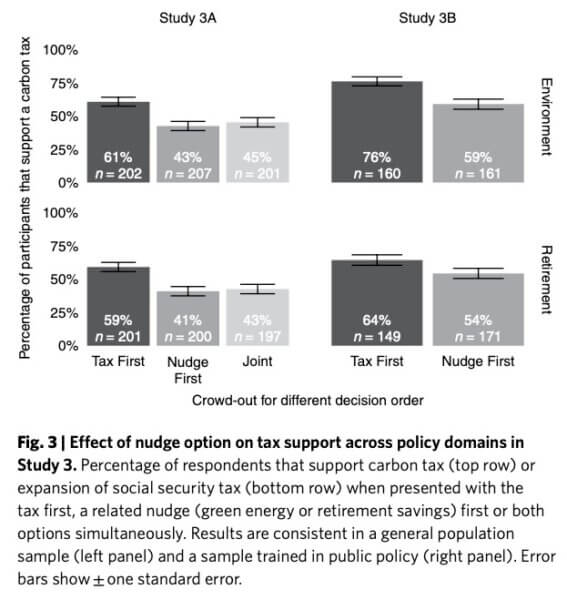

A second way sustainability misinformation is working against sustainable development is via green nudging.

When ineffective, but perhaps easier policy comes before the effective but harder policy, the effective policy is less likely to be successful. If the effective policy comes first, the chances of success are much greater.

One example here could be carbon pricing, well supported by the scientific evidence to be an effective strategy for climate change mitigation.

Having policy that focuses on things like carbon footprinting, which is widely debated as an effective strategy come before as we’re currently doing, when we finally get to the carbon, pricing is going to be an increasingly uphill battle.

All of this is to say the order of policy in environmental action in general matters. Therefore, relying on the best available evidence is crucially important as we pursue sustainable development.

One final thing I want to add is that if we want to make significant strides towards sustainability, what we really need are science-based policy changes.

Consumer scapegoating and corporate sustainability aren’t working. We’ve seen this with carbon pricing, which as mentioned is one of the more well supported policies for addressing climate change. But instead of focusing on implementing it effectively, there’s a lot of blame on consumers and a lot of focus on things like carbon footprinting, which has incentivized a pretty problematic market for carbon offsets, which is yet another whole complex topic I won’t get into here.”

Sustainability is obviously a huge topic, so we only covered a tiny fraction of it here! Let me know what other parts of sustainability you want to know more about.

In the meantime, you can check out Jen’s many podcasts and Instagram posts on sustainability.

References

CO2 is main driver of climate change. Skeptical Science. Published July 15, 2015. Accessed May 2, 2023.

Teigiserova DA, Tiruta-Barna L, Ahmadi A, Hamelin L, Thomsen M. A step closer to circular bioeconomy for citrus peel waste: A review of yields and technologies for sustainable management of essential oils. J Environ Manage. 2021;280:111832. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111832

Dell’Acqua G. Garbage to glamour: recycling food by-products for skin care. Cosmetics & Toiletries. Published February 6, 2017. Accessed May 2, 2023.

2021 Sustainability Record (GRI). Symrise; 2022.

Pacheco R, Huston K. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of naturally-sourced and petroleum-based glycols commonly used in personal care products. SOFW Journal 2018;144:12-15.

Herbes C, Beuthner C, Ramme I. Consumer attitudes towards biobased packaging – A cross-cultural comparative study. J Clean Prod. 2018;194:203-218. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.106.

Biodegradable Plastics Association. Denkstatt Report. 2011.

Novakovich J. “Sustainable” Packaging with Dan Coppins Podcast. The Eco Well. Published January 26, 2022.

Novakovich J, Coppins D. Sustainability in Packaging Fireside Chat. Presentation at: Sustainable Beauty E-Summit; March, 2022.

Kades A. Tetra Pak points to carbon impact as Morrisons’ milk carton switch raises recyclability concerns. Packaging Insights. Published March 4, 2022. Accessed May 2, 2023.

Vaclavova B. Morrisons doubles down on switch to Tetra Pak milk cartons. letsrecycle.com. Published August 22, 2022. Accessed May 2, 2023.

Wiedmann T, Lenzen M, Keyßer LT, Steinberger JK. Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3107. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y

Haberl H, Wiedenhofer D, Virág D et al. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15:065003. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

Competition and Markets Authority. Guidance: Making environmental claims on goods and services (Green Claims Code). Published September 20, 2021. Accessed May 2, 2023.

Liszewski W, Zaidi AJ, Fournier E, Scheman A. Review of aluminum, paraben, and sulfate product disclaimers on personal care products. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(5):1081-1086. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.840

Ford AT, Ali AH, Colla SR et al. Understanding and avoiding misplaced efforts in conservation. FACETS. 2021;6:252-271. DOI: 10.1139/facets-2020-0058

Hagmann D, Ho EH, Loewenstein G. Nudging out support for a carbon tax. Nat Clim Chang. 2019;9:484–489. DOI: 10.1038/s41558-019-0474-0