Is synthetic braiding hair giving people cancer? In February 2025, Consumer Reports announced that they had found carcinogens in all 10 products of artificial braiding hair they tested. They claimed this was putting the health of wearers and braiders at risk. But is this actually true, or is it fearmongering?

Here’s the video version – keep scrolling for the article.

Overblown results are harmful

First off, I think this is a really important area of research. Traditionally in science, the further away from white and male we get, the less data we have. So it’s great that Consumer Reports is testing products a lot of black women use.

But it’s also a bigger problem if the results aren’t presented in an honest and transparent way. People might be encouraged to take unhelpful actions, which makes the problem worse.

It’s like we didn’t know if we should worry about bears or sharks. New research shows there’s only one shark, and he’s actually kind of pathetic. But if the results are hyped up, people are now spending all their energy building shark-proof nets and writing petitions to hire more lifeguards. Everyone’s forgotten about the bears!

And in my opinion, that’s exactly what’s happening with these Consumer Reports results.

Dangerous chemicals?

The headline:

Dangerous Chemicals Were Detected in 100% of the Braiding Hair We Tested.

We sent to the lab 10 of the most popular synthetic braiding hair products on the market, from brands including Magic Fingers, Sassy Collection, Sensationnel, Shake-N-Go, and others. Carcinogens were detected in all of them.

If you’ve watched my videos before, you’ll know there’s one crucial detail left out: how much of these chemicals were there?

In toxicology, there’s a saying: “the dose makes the poison”. If you have enough of anything, it can be harmful to your health.

Related post: Clean Beauty Is Wrong and Won’t Give Us Safer Products

The flip side: if you have a small enough amount of anything, it won’t be very harmful. For example, we all have about 90 micrograms of radioactive uranium inside our bodies, but this is fine because it’s such a low amount – the chance of it interacting with enough things inside our bodies to have an effect is minimal.

Top findings

Consumer Reports gives these as their top findings:

- Carcinogens, or chemicals that may cause cancer, were detected in 100 percent of the samples.

- Lead was detected in nine of 10 products.

- Other VOCs, including acetone, were detected in all products.

We have numbers, but these aren’t useful.

Simply detecting substances doesn’t mean much. Chemists are getting better and better at measuring things, and atoms are ridiculously tiny. There’s probably more atoms in a pack of braiding hair than there are grains of sand on earth.

In the 10th sample, I’d bet that at least a few of those atoms are lead – we just don’t have the technology to detect it yet, and the amount is so low it’s not concerning. So these “top findings” are very unhelpful, and to me it’s weird that Consumer Reports picked these as their “top findings”.

Carcinogens

The first category of substances are carcinogens (cancer-causing substances)

All 10 products had more than one carcinogen. The article tells us benzene is “a known carcinogen that causes acute myeloid leukemia,” and “is strictly regulated and discouraged to use in laboratories because of its potential to cause cancer”. They also say “two products contained an animal carcinogen, and all the samples contained a probable carcinogen, methylene chloride”.

Below this is a chart listing the carcinogens in each product, divided into known, probable and possible. These IARC categories simply tell us about the certainty of evidence, not how concerning they should be (I’ve discussed these in the context of benzene before).

Related post: Benzene in your products, Part 1: Bad science

We need to click into the “full test results” to see the amounts – which is where the juicy stuff is.

Benzene

There are two benzene measurements for each sample. Benzene was detected 4 times out of 20, 15-18 micrograms per kilogram (μg/kg).

For a long hair style, it seems like you might use maybe a pound (around 0.5 kilograms) of hair. According to these results, this would contain less than 9 micrograms of benzene.

Is this scary?

I’ve talked about benzene before – it’s an air pollutant that we all breathe in every day. It comes from many sources, including petrol, so it’s pretty unavoidable. But not everyone gets leukemia despite breathing it all day every day (and breathing it is generally the main concern – it doesn’t go through skin easily). So it isn’t really a concern unless you get a lot of exposure (again, dose is critical), for example if you’re a mechanic, or if you work at a petrol station.

Let’s put the amount in synthetic hair into context:

- If you live in a city, you inhale around 60 micrograms a day. This is 6 times the maximum amount in 0.5 kg of hair.

- You’re not inhaling all of the hair (unless things are really not going well for you), so most of the benzene would be drifting off into the air.

- Braided hairstyles typically last weeks or months. If we go with 4 weeks (28 days), that works out to be an average of 0.32 μg a day.

Related post: Benzene in your products, Part 1: Bad science

Some extremely hi-tech scale drawings:

- Bar 1 (dark blue): 60 μg = benzene you breathe in every day.

- Bar 2 (red): 9 μg = benzene in half a kilo (1 pound) of hair, which you don’t completely breathe in (hopefully)

- Bar 3 (pink): 0.32 μg = the extra benzene you might inhale each day from the hair, on average over 4 weeks (daily benzene is 187 times higher)

- Bar 4 (light blue): 100 μg = benzene produced while cooking on a gas stove

- Bar 5 (green): 110 μg = benzene inhaled on average while filling your car up for 5 minutes

The last two are 300 and 340 times more than the amount in 0.5 kg of synthetic hair.

And these higher numbers are everyday amounts of benzene that don’t cause leukemia, the vast majority of the time. So do we really need this much hype about scary benzene and leukemia? Consumer Reports have been around for a long time, so I would think they’d know what framing gets traction, and this is indeed what you see in the news headlines and on social media.

Benzene exposure for braiders?

When I posted about this on Instagram, some people asked if braiders cleaning hair in hot water might be a concern – here’s another risk estimate.

A few braiders (including former braider’s apprentice Dr Siobhan Oma) kindly gave me estimates for hair usage and clients per day:

- Packs of hair weigh around 60 g (16 inches) to 100 g (26/30 inches), a “jumbo pack” weighs 165 g

- 2 to 6 packs of hair are used per head

- Number of clients per day depends on skill and style, as well as whether braiders team up – maybe 3-5 clients per day

- 5 packs on each of 5 heads will be 2500 g or 5.5 pounds

To be safe, let’s say a braider boils 10 pounds of the worst hair for 10 minutes – this releases 81 μg benzene.

If someone was trapped with this amount in a perfectly sealed small bathroom (8 x 8 x 8 ft) daily for 78 years, the increased chance of cancer will be roughly 3 in 100,000 (extrapolating from the EPA’s inhalation risk for 5.6 μg/m3).

It’s really difficult to seal a space this well (I’ve been in a lot of spaces with an Aranet4 – ventilation monitoring is kind of a hobby of mine). And if you’re boiling water, a sealed room would be super humid. Anyone in this situation would think to open a window or turn on the fan.

And there are other hazardous chemicals that would build up much faster under these conditions. The focus on benzene distracts from investigating those, and distracts from pushing for safety measures aside from testing hair for benzene.

I would be completely behind a petition to increase ventilation education – it reduces the risk for pretty much any detrimental substances in the air (including pathogens). Again, the problem is that Consumer Reports directs all focus to the not-very-scary shark.

Related post: Nail Polish, Miscarriages, Cancer? Not So Pretty Episode 2

Methylene chloride

The other carcinogen they name is methylene chloride, also known as dichloromethane. This solvent is used in paint stripper, and it’s a common lab solvent (I used a ton during my research, with safety precautions). It’s not good for you in high amounts – there are some “burst” gel polish removers you can buy online that contain dichloromethane, and I’d recommend against using those.

But the amounts in synthetic hair?

Consumer Reports found that in their samples, it’s mostly under 20 μg/kg, with an unusually high measurement at 54 μg/kg (the other measurement for that product was 19 μg/kg, which is a huge difference – this raises the question of reliability, and in a regular scientific study you’d want to go back and remeasure).

We’ll use 54 μg/kg – that gives us 27 μg of methylene chloride in half a kilo of hair. This is about 1/2500th of one drop (1 drop = 0.05 mL, density = 1.33 g/mL).

For comparison, the Australian safe work guidelines allow 1.74 million μg a day to be inhaled (174 mg/m3, based on 10 m3 inhaled air a day). I’m not saying we should all go inhale this much every day for fun, but we need perspective here – over 60,000 times as much as the total amount in the worst synthetic hair is still considered relatively okay daily exposure.

The Australian drinking water guidelines allow 0.004 mg of methylene chloride per litre of water. This means that if one million people drank 8 μg of methylene chloride every day for 70 years, less than one person would be expected to get cancer from it. If we divide the amount in half a kilo of the worst synthetic hair by 28 days, that’s 0.96 μg – 8 times less. Again, the hair isn’t all ingested, so this is well under a one-in-a-million increased chance of cancer – not that concerning.

Again, Consumer Reports’ tests show that the shark is pretty pathetic if you crunch the numbers – but that’s very different from how they presented it.

Heavy metals

Next is heavy metals, and Consumer Reports do talk about dose this time:

None of the products had detectable arsenic. “Three of the products had detectable cadmium, but our exposure and risk analysis found the levels did not pose a risk,” Rogers says.

Lead, however, was detected in nine of the 10 products. “Our exposure and risk analysis found all nine products could expose a regular user of any of these products to a level of lead that could be concerning over time,” he adds.

Is this actually true?

Lead is bad, and they talk about some of the issues (brain and nervous system damage, immune system suppression, reproductive issues, kidney damage, hypertension, developmental problems in children). I’m no fan of lead – it’s one of the reasons I don’t grow my own vegetables. I currently live in the Inner West of Sydney, where there’s been pretty high leads levels reported (you might want to look that up in your area).

But the amounts in synthetic hair – this time, Consumer Reports show the amounts in the main part of the article, in a table. Here’s the top and bottom rows:

The lead level is shown as a percentage of the Maximum Allowable Dose Level (MADL). One product had no lead detected (again, it still probably has lead), while the rest had between 123 and 610% of the MADL (1.2 to 6.1 times the MADL).

What is the MADL? Consumer Reports say it’s “the level deemed safe by experts”, but they say there’s no official limit for lead in braiding hair, so their scientists picked California’s food limit as the point of comparison, because it’s the “most protective” in the US at 0.5 μg of lead a day.

They considered looking at inhalation, skin contact or eating, and they chose eating. Their logic is that braiders can accidentally eat hair that’s broken off, and small children might chew on their hair, which is fair enough.

But how much are Consumer Reports assuming you’d eat to reach these amounts of lead?

They do not explicitly say this, so I messed around with the numbers in the table. It looks like they averaged the two numbers for each sample, worked out how much you would get if you eat 25 grams of hair, and compared it to the MADL.

I didn’t have synthetic hair on hand, but this is 25 grams of acrylic yarn – slightly larger than a tennis ball:

MADL describes what’s safe to eat every day, long term – I really don’t think this is realistic, even for kids chewing their own hair.

If 25 grams is eaten every day, a full head of braids (0.5 kg) would be completely gone in 20 days. If this is happening, I don’t think the lead should be your main concern.

California’s MADL is the lowest in the US:

- Australian drinking water guidelines allow 10 μg of lead a day (based on a 2 year old drinking 1 L/day), 20 times higher than the MADL. You’d need to eat 80 grams (3 balls) of the most leaded hair each day to reach this level.

- The US FDA’s level for children is 2.2 μg – you’d need to eat the big half a ball of the most leaded hair a day to reach this level (I know everyone thinks US stuff is dangerous but a lot of the time they actually have lower limits).

Let’s compare this to soil, which young kids are much more likely to swallow (e.g. I was at the bank a few weeks back and a toddler was eating the carpet).

The lead in soil in the Inner West can be tens of thousands of times higher than the worst synthetic hair (960 mg/kg). Eating 2 milligrams of this soil will reach the FDA allowable limit.

If the dirt was meeting the safe Australian guideline of 300 mg/kg, you’d need about 7 milligrams of dirt.

A TicTac is about 500 milligrams. Not to make you paranoid about soil (these FDA levels do have big safety buffers built in), but a tenth of a TicTac’s worth of soil has similar lead content to half a tennis ball of the worst synthetic hair. Is synthetic hair really the dangerous source of lead we should be focusing on?

Volatile organic compounds

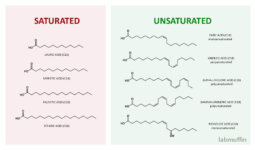

Then we have volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – these are “whiffy” liquids you might inhale like solvents, petrol, and alcohol. More of these evaporate with heat, and synthetic hair is sometimes heated during washing, or during the braiding session.

Consumer Reports’ chart shows the “total number of VOCs measured” – I think they meant the total mass of VOCs. This was measured after sealing the hair in a flask and boiling it in water for 10 minutes.

There are some big differences from real life:

- Braids are usually dipped for far less than 10 minutes (usually maybe 10 or 15 seconds)

- VOCs are gases, so ventilation makes a massive difference – sealing the tube means you can properly measure the full amount, but that’s less relevant to real life

I don’t think adding the VOCs together is useful. The report says: “The higher the total number of VOCs in a product, the higher the likelihood of a negative impact on the health of the user”.

I completely disagree with this, because different VOCs have different effects. For example, drinking one shot of ethanol (drinking alcohol) is much safer than one shot of methanol (wood alcohol) – it’s the same with inhaling different VOCs.

The main VOC they measured in every sample was acetone. 5 samples had at 390,000-5,900,000 μg/kg and 4 samples had 120-290 μg/kg. The other VOCs were under 830 μg/kg (the vast majority were under 100 μg/kg).

But acetone is a very safe substance. While it can be a respiratory irritant if large amounts are inhaled, we exhale it when we burn fat for energy. It’s commonly used as nail polish remover.

0.5 kg of the “worst” hair produces 2.625 g acetone when boiled for 10 minutes. If this is all evaporated and inhaled at once, it wouldn’t be very pleasant – but you’d notice the smell before it would have serious health effects, and you’d do it somewhere more ventilated (it would also be dripping wet from the steam). If all of this evaporated into a sealed box the size of a large fridge, and you were inside breathing it for 8 hours, you’d hit Australia’s safe work guideline, and the main issue is just irritation.

So this huge contribution from acetone means that Consumer Reports’ chart actually distorts the relative risks from different products. The “worst” products (6 million) look far more dangerous than the “best” (300).

This is what the chart looks like if we subtract acetone:

I’ve never heard of any of these brands before, so I’m not trying to make specific brands look better – but the numbers are a lot more similar:

- Hbegant and Darling are around the same now, even though with the acetone Darling looks thousands of times worse

- The worst product now is Shake-N-Go FreeTress, which was in the top half before – it has about 3 times more combined VOCs as the next highest product

Note that these numbers are still misleading, since the other VOCs are still all conflated, but it makes a bit more sense – I would say styrene is higher risk than acetone. But these VOC levels are very low – to reach the safe work limit, the highest level of styrene in 0.5 kg of synthetic hair would all have to evaporate into a 833 mL box (around 3.5 cups), and you’d need to huff it for 8 hours.

Actual risks?

At the very top of the Consumer Reports article, it talks about the background: a student called Chrystal Thomas wrote a commentary paper about synthetic hair after she had braids done. Her throat felt irritated, and the synthetic hair smelled very strong even after washing multiple times.

These effects aren’t explained by the Consumer Reports results. Extremely low amounts of benzene, methylene chloride, lead, styrene, and higher (but still low) amounts of acetone would not have these effects, especially for multiple days and after multiple washings – the bear is still out there.

A more accurate way of framing the findings, in my opinion: “Synthetic hair might be unsafe, but it’s not because of any of the carcinogens, heavy metals or VOCs Consumer Reports tested for.”

It’s really not as exciting though, is it?

Some more likely culprits are suggested at the bottom of the article:

- Rashes and swelling: This could come from irritants or allergens. Some people have raised the issues of irritating coatings on synthetic hair, which is why it’s often washed with hot water or cleaning solutions before use. In terms of allergens, my guess would be perhaps acrylates – allergies to these are rising with home gel kits.

- Tight braids is a big issue – as well as pain, they can cause hair loss (traction alopecia).

- Other potentially toxic ingredients: Synthetic hair doesn’t really count as a cosmetic product, so there’s a lot less ingredient list transparency.

Related post: Are gel nails bad for you? UV, skin cancer and allergies

Again, I think it’s fantastic that Consumer Reports are researching braiding hair. But their presentation of the findings shifts focus to the wrong risks.

Some news article around this report stated that “black women deserve better”, and I agree. But they don’t just deserve better products and more research – they also deserve not to be misled by hyped up questionable findings.

Consumer Reports’ petition to the FDA advocates for the FDA to “investigate synthetic braiding hair and set strict standards for these products by limiting dangerous chemicals—especially known carcinogens, such as benzene—and heavy metals, including lead.”

But their results actually show that benzene and lead aren’t a concern!

In science, it’s disappointing when your hypothesis doesn’t pan out after time-consuming research. But negative results are useful and valuable, and necessary for progress.

Misrepresenting them is the opposite. It distracts from other risks – people are still having reactions to synthetic hair. Consumer Reports should really petition the FDA to look at other substances, or petition representatives to increase FDA funding (deregulation of US public health institutions is currently happening at an alarming rate).

A little rant about Consumer Reports

I wasn’t that familiar with Consumer Reports before, aside from their annual sunscreen testing results which are really interesting (although those are also sometimes taken out of context).

They tend to do more reporting around food, and it turns out they have a longer history of really exaggerating the risks they found there, similar to what they did with this synthetic hair story. (This article on heavy metals in chocolate by the excellent Food Science Babe is where I learned about the FDA lead guidelines.)

In the last few years, Consumer Reports have published more stories on personal care products, and it feels like they’re going down the fearmongering pipeline.

Related post: Clean Beauty Is Wrong and Won’t Give Us Safer Products

In December 2023 they posted about baby wipes in conjunction with a company called Made Safe, which seems to be an even crappier version of the EWG. Their science advisors include:

- Multiple naturopaths – Naturopathy is not science. A handful of natural remedies do work, but naturopathy promotes many that don’t, and are actually dangerous. There’s a common misconception that it’s simply conventional medicine plus natural things, but naturopaths are not taught actual science (more on naturopaths from Science-Based Medicine and a former naturopathic doctor).

- Dr Mark Hyman – a notoriously bad source for anything medicine or science.

- A “Detox Expert”, a “Herbalist”, a “Wellness Instructor”, and a doctor qualified in “homeopathic medicine”

This is an extremely wild collection for a science advisory board, and it’s no surprise that all of Consumer Reports’ collaborations with Made Safe are also full of bad advice.

Fearmongering is harmful

Since publishing the video version, I’ve noticed a lot of comments about how people are now completely reassured about the safety of synthetic hair – despite me making conscious efforts throughout the video to highlight unanswered questions about their risks, that still need investigating (whether there are “bears”).

I’ve seen similar situations play out with other sensationalised headlines. In my opinion, this is because people have been so intensely focused about specific risks that when they hear those are overblown, it’s all they can think about – the rest of the message is lost. It’s yet another way that sensationalised framing works against the shared goal of improving safety and health outcomes.

References

Jackson LA. Dangerous Chemicals Were Detected in 100% of the Braiding Hair We Tested. Consumer Reports. February 27, 2025.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Uranium. 2013.

US EPA. Benzene; CASRN 71-43-2 I. Chronic Health Hazard Assessments for Noncarcinogenic Effects I.A. Reference Dose for Chronic Oral Exposure (RfD). April 17, 2003.

Rouillon M, Harvey P, Kristensen L, Taylor MP, George SG. Elevated lead levels in Sydney back yards: here’s what you can do. The Conversation. January 16, 2017.

Safe Work Australia. Non-Threshold Based Genotoxic Carcinogens: Accessory Document to Recommending Health-Based Workplace Exposure Standards and Notations. 2018.

Safe Work Australia. WES Methodology: Recommending Health-Based Workplace Exposure Standards and Notations. 2018.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Drinking Water Guidelines 6 2011 (Version 3.9 Updated December 2024). 2011.

Garrett B, Caulfield T, Murdoch B, et al. A taxonomy of risk-associated alternative health practices: A Delphi study. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(3):1163-1181. doi:10.1111/hsc.13386

Schoon D. Facebook Post on burst gel removers. October 11, 2019.

Balch B. Why we know so little about women’s health. AAMC. March 26, 2024.

Food Science Babe. Are there dangerous levels of heavy metals in dark chocolate? AGDAILY. January 18, 2023.

Samantaroy S. ‘A Machete Rather Than A Surgical Knife’: Critics Deplore The Mass Layoffs At NIH, CDC, FDA. Health Policy Watch. February 21, 2025.

Bellamy J. Goop and Dr. Mark Hyman join forces for some functional medicine heavy metal fear mongering. Science-Based Medicine. November 8, 2018.