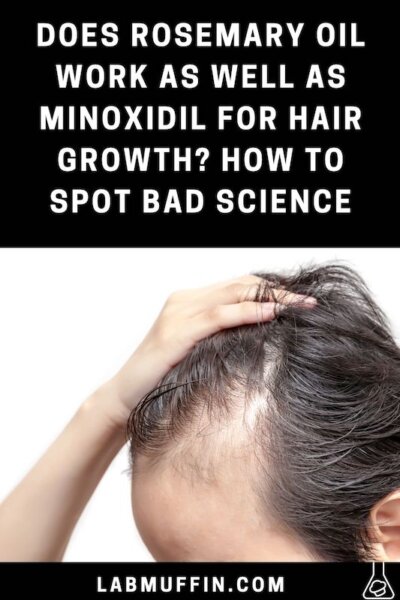

Is rosemary oil a natural, science-backed treatment for hair growth?

According to a lot of doctors, scientists and trichologists across the internet, yes – there’s “scientific proof” that it works as well as minoxidil. But unfortunately, that isn’t true.

It all seems to be a misunderstanding of a single study: Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial.

For a long time I didn’t look into this study – I just assumed it was legitimate, at least on the surface, because so many perceived experts cited it.

A lot of the time only having one study is a bad sign, since the finding hasn’t been replicated. But science isn’t a democracy, and sometimes one really good study can be convincing…

So when I finally read the paper, I really wasn’t prepared for how bad it was! And this made me realise how little people know about interpreting scientific evidence.

In this article, I’m going to explain:

- Why the study is terrible

- What the science actually tells us about rosemary oil and hair loss

- Whether rosemary oil is worth trying, and what you can try instead

I’ll also be giving you some tips for critically assessing studies, so you don’t fall for bad science.

The video version is here – the article continues below.

The abstract

A lot of people talking about this study seem to be basing their opinion on the abstract, and assuming the study must be good since it was published in a peer-reviewed journal. These are both terrible ideas – I go into more detail on peer review and problems with relying solely on abstracts in other articles.

This paper’s abstract sounds pretty good, at first glance:

- Sample size: There’s a total of 100 people, which is a lot for a cosmetic study. More subjects means more repetition, so the results are less likely to be a fluke.

- Study length: The treatments were used for 6 months, which seems like a reasonably long time.

- Use of a comparison: Rosemary oil is being compared with minoxidil, one of the most popular hair loss treatments. This isn’t as good as comparing it against a placebo treatment containing no active ingredients. But many cosmetic studies only have people using the treatment, so again, it seems promising.

Here’s the result that sounds really impressive:

“Both [the rosemary oil and minoxidil] groups both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at the 6-month endpoint […] No significant difference was found between the study groups regarding hair count either at month 3 or month 6”

A word of warning: in science, “significant increase” doesn’t mean there was a lot more hair. It means that the finding is statistically significant – basically, the increase is pretty likely to be because of something actually happening, rather than just random variation.

Statistical significance doesn’t tell you the size of the increase – it could still be really small (e.g. three extra hairs). Scientists sometimes use words weirdly. It’s another of the many traps you can fall into when reading papers.

Related post: Why you can’t trust study abstracts

So if the abstract was all you read, and you assumed it was accurate, rosemary oil sounds really promising.

Let’s ruin it all by reading…

The actual paper

Here are the standard parts of a scientific paper (arranged here from top to bottom, then left to right):

The most important parts to read are the methods and results – these tell you what original research the authors did. They’re the whole point of the paper.

- These are usually the hardest bits of the paper to read and evaluate. They’re more technical, with more complicated words, numbers, and undefined acronyms. And you generally need to know a bit about the area already to assess these sections to any proper level.

- The methods and results are also the parts most closely checked by peer reviewers, if the whole process goes right.

The abstract, introduction, discussion and conclusion are much friendlier to read. They have mostly normal words and tell a nicer story. But they’re the authors’ interpretations of their research – these are more subjective, and more liable to spin.

- The introduction is the background, so if the peer reviewer is an expert in that field already, they’ll probably just skim it. They probably won’t make sure every reference that’s being cited is actually supporting their statements. It’s also more general, so the researchers probably don’t have as much expertise in the broader field than they do for the specific topic of the paper.

- The discussion and conclusions talk about their interpretation of the results and their implications, puts it into context, and includes any limitations. If the interpretation here is sus, it’s a huge red flag – but before we can judge if the interpretation is right, we need to look at what it is we’re interpreting.

All of this might sound really intimidating, like only active scientific researchers can spot bad science. But I don’t think that’s the case.

In my 12 years of interpreting and talking about cosmetic science, I’ve noticed that papers with major problems with their experimental methods usually messes up in other places too. So you don’t actually need to be that familiar with the nitty gritty of the experimental methods to flag a paper as sus, and something you probably shouldn’t view as convincing evidence. And this rosemary oil paper is a really good example.

Dermatological red flags

I read this paper after seeing an Instagram post from Dr Leona Yip, an Australian dermatologist. She pointed out some of the problems with this paper, which a few other dermatologists have flagged as well. Dermatologists don’t just deal with skin conditions, they also specialise in hair and nails – or at least the bit that’s living, which is very much the part involved in hair loss!

Problem 1: 2% minoxidil

Minoxidil is one of the best studied treatments for hair loss, which is why this paper sounds so impressive – but the detail here is the concentration used.

Dr Leona Yip (@drleonayip_dermo): “The vast majority of dermatologists recommend at least minoxidil 5% to grow hairs because 2 percent is just too weak. I honestly don’t even remember myself when I had asked a patient to use minoxidil 2% in the last 10 years, because I think they’ll be quite disappointed.”

Dr Mark Strom (@dermarkologist): “We know that 5% minoxidil has much better efficacy when compared to 2% minoxidil, so rosemary oil is really compared against the weaker treatment.”

Problem 2: The study duration

6 months might sound like a long time, but it’s not a long time for hair growth – 6 months is actually considered really early.

Dr Leona Yip: “With any effective treatment, it takes at least 3 to 6 months to start showing early effects. And to see visibly meaningful regrowth or hair thickening that most people would be happy with, this may take at least one to two years. I suspect if we looked at the two year mark, minoxidil 2% will likely be more effective than rosemary oil.”

General red flags

But there are more general red flags in this paper too.

Here’s one I think anyone can spot: the sample before and after photos aren’t very impressive, and the minoxidil photos seem to be showing different angles, with a weird shadow at the bottom. This really reinforces what these dermatologists were saying – you don’t really expect much of a result after 6 months with 2% minoxidil.

But the thing that really blew my mind, and stopped me from taking this study as evidence of, well, anything, were the reported hair count numbers:

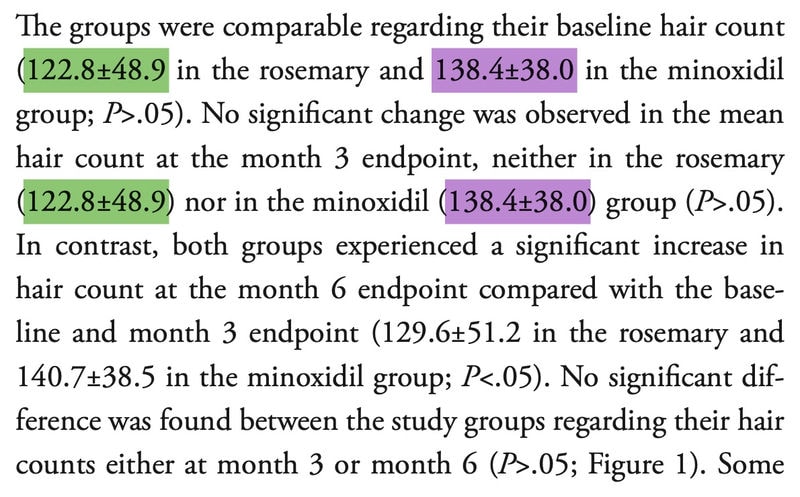

At both the start of the trial and at 3 months, the hair counts were 122.8±48.9 in the rosemary group, and 138.4±38.0 in the minoxidil group.

This has to be a typo. It’s basically impossible to get the exact same mean and standard deviation for two groups of 50 people, 3 months apart – you probably couldn’t even get exactly the same numbers an hour apart.

And whoever turned this data into a graph also didn’t see an issue with these numbers, and used them to make the graph – baseline and month 3 are exactly the same.

Obviously, typos don’t mean the study is automatically untrustworthy – I have typos all the time in my posts! But these are typos with two of their key data points. There are only 6 numbers that the main findings rely on, and two of them are wrong – can we actually trust the other 4 numbers?

This paper has 4 authors who supposedly all looked over these numbers, and approved both the text and the graph. The journal editor and peer reviewers supposedly looked over it too, and no one corrected them. This is the sort of error I’d expect a peer reviewer to pick up immediately. If I were reviewing this, I’d be asking to see the raw data, and checking their calculations.

It’s bad enough if we assume the Month 3 numbers are wrong, but it could actually be the baseline numbers, which are what “significant increase in hair count at the 6-month endpoint” is based on.

I haven’t been able to find any corrections of this, or any indications that other researchers have asked the authors for clarification, even though it’s been cited 93 times as of February 2024 (we’ll come back to this later).

Lots of little basic errors

As well as these issues with these key results, I keep seeing new errors every time I look at the article. I’m not great at stats, and I haven’t checked every single word, so I’m sure there’s more things I haven’t picked up…

Some of the results reported don’t match the data in Table I:

- The mean age of the 100 subjects as calculated from the table data would be 24.08, not 24.03

- 16 plus 13 men had Stage III AGA – out of 100 men that would be 29%, not 21%

Figures 5 and 6 are meant to be for greasy hair and dandruff, but they’re the exact same (well, the formatting is a few pixels off). If you look at the result paragraph above, dandruff should have much lower numbers (16% in the total study population), so Figure 6 seems to be the incorrect one.

These figure references are wrong – Figures 5 and 6 aren’t about scalp itching, that’s all in Figure 7:

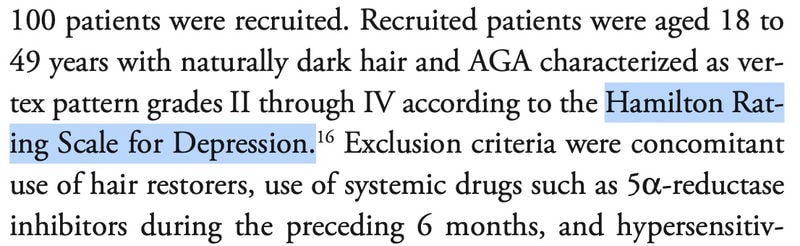

And you don’t use a rating scale for depression to measure hair loss. Depression and hair loss are completely different medical conditions:

This all highlights what I was saying before – a paper with serious methodological issues tends to have lots of other issues. You don’t need to spot all of these to know that this paper isn’t reliable (it actually feels like I’m going against years of my training to keep closely reading this paper when it’s already so clear there isn’t anything to be gleaned from it).

And again, some typos are fine – lots of good papers can have mix-ups, they can happen during the final stages of formatting, and a good journal will issue a correction and everything’s fine.

But a whole bunch of issues are a huge red flag that something isn’t right. And the calculation errors here are particularly concerning – the full dataset isn’t available, so you have to trust the authors did the calculations correctly to trust their reported results (and how they conducted their experiments).

Are the results impressive?

The absolute numbers

Even if we assume the reported baseline and month 6 numbers are correct, it’s still really not very impressive.

The average difference for rosemary oil and minoxidil after 6 months is 6 and 2 hairs respectively, in groups where the standard deviation is up to around 50. The average hair count increased by only 5.5% in the rosemary group, while minoxidil increased by 1.6%.

And the graphical version of the results shows how small this difference is – if you had to just eyeball the difference between the Baseline and Month 6 columns, it would be hard to say which was higher (I’ve included the overlay underneath so you can actually tell).

Is this a real effect?

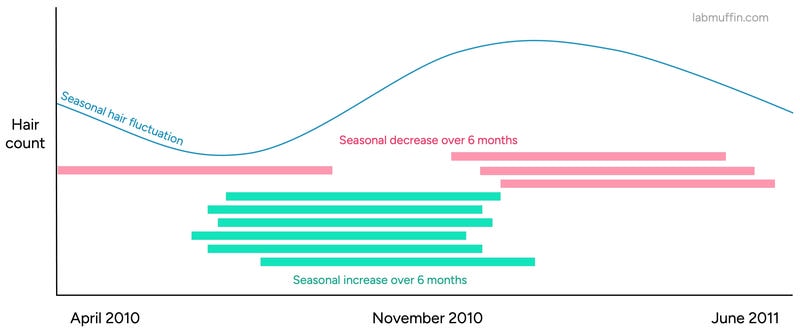

This is already pretty unconvincing, but it’s compounded by the fact that hair count naturally fluctuates.

There are three stages of hair growth – anagen, catagen and telogen. Our hair is distributed into these three stages, so we have more or less consistent shedding… but it isn’t completely consistent.

Most people have a bit more hair in spring, with more hairs are in the anagen stage, while shedding tends to increase in autumn, with more hairs are in the telogen stage. It’s like a weak version of how some animals shed their winter coats. For some people, this can lead to noticeable shedding in autumn.

This study took place between April 2010 and June 2011 in the Northern hemisphere. So if you had a few more people participating in the trial in the middle (starting around June 2010) than towards the start or end of the trial period, you’d see an increase in hair count even if the treatment wasn’t having any effect, as illustrated below:

And if you look at the hair count changes for the placebo treatment in other studies, where there’s no active ingredient being used, you can sometimes see similar fluctuations.

In this study, the placebo group goes from an average of 132 to 191 hairs over 4 months – an increase of 45%. Minoxidil 2% gave an increase in terminal hair count of 123% (130 to 290) over 6 months.

As well as seasonal variation, a measured increase in the study could also be explained by other factors, such as the fact the subjects were massaging their scalps twice a day, or something else in the lotion (the composition isn’t given in the study).

Anecdotal evidence?

These seasonal fluctuations could also explain why so many people on social media claim that rosemary oil worked for them.

There’s also the fact that sudden hair loss often happens because of a specific stressful event. This is called telogen effluvium, and it’s common with covid as well as a myriad of causes like sudden weight loss or surgery. After the stressful event stops, your hair will gradually grow back.

But people often try new remedies like rosemary oil when their hair is at its worst. So they’ll see their hair grow back right after trying these, and it’ll look like the treatment is working, even if the hair was going to grow back at that point regardless. This is called regression to the mean (see this article on anecdotal evidence).

Related post: Science vs Anecdotal Evidence and Reviews

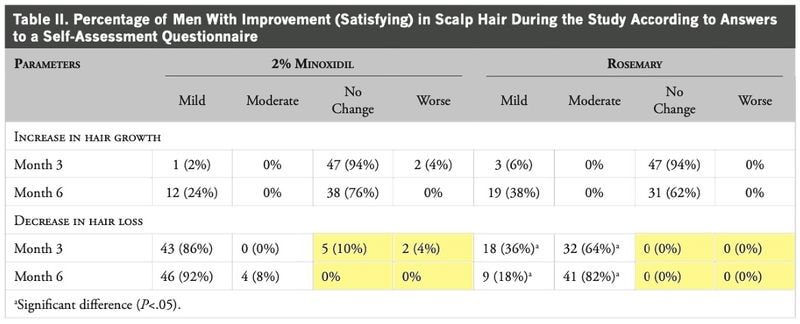

With anecdotes, there’s also the issue of perception. A lot of factors impact whether we think something works. This can be seen in some hair loss studies, where the subjects were asked whether they felt like their hair loss improved, in addition to recording objective hair count data.

For example, in this study, 11 out of 180 people being treated with 5% minoxidil (6.1%) felt like their hair loss was worse after 16 weeks, even though none of them had worsened hair loss according to photographic data.

And as you’d expect for a treatment that probably doesn’t have much of an effect, there are also heaps of people on social media saying rosemary oil made their hair loss worse.

In this rosemary oil study, the self-assessment data does seem to be yet another red flag.

- Everyone in the rosemary oil group said their hair loss decreased at both 3 and 6 months

- Everyone in the 2% minoxidil group said their hair loss decreased at 6 months, while 7 people said there was no change or it got worse at 3 months

Even in studies using 5% minoxidil, a far more proven hair loss treatment, there’s a greater proportion of people saying there was no change or worsened hair loss in self-assessments, even with much larger actual improvements in hair count:

And again, it just seems like something very weird is going on in this study.

Conclusions on this clinical trial

I don’t think this study actually tells us much at all. The most generous thing we could say, in my opinion, is that in a study with really sus numbers, where a low concentration of minoxidil unsurprisingly didn’t do much, rosemary oil also didn’t do much.

Other evidence for rosemary oil?

If the only clinical study on rosemary oil and hair loss is pretty unconvincing, what are we left with?

The introduction and discussion mentions why they chose rosemary oil in the first place – it could potentially work in ways that are thought to improve hair loss (it has potentially beneficial mechanisms of action).

It could perhaps increase blood flow to hair follicles:

“Since the spasmolytic activity of rosemary may enhance microcapillary perfusion, this plant has been hypothesized to increase hair follicle blood supply, thereby being effective for the treatment of AGA [androgenetic alopecia, or male pattern hair loss].”

And it’s an antioxidant, which could neutralise reactive free radicals, which could potentially be contributing to hair loss:

“Another mechanism for the beneficial effects of rosemary oil is its antioxidant activity. Oxidative stress has been suggested to be associated with alopecia as significantly lower levels of antioxidants and elevated oxidants have been found in patients with alopecia.”

The problem with relying on this sort of reasoning: there are a lot of mechanisms happening inside your body, and they can have completely opposite effects.

I talk more about mechanistic reasoning in this article – in short, thousands of drug candidates with much better mechanistic evidence and convincing animal testing data than rosemary oil didn’t end up working in humans.

Related post: Why “scientific” products don’t always work: mechanistic reasoning

That’s why properly approved drugs like minoxidil are really the first point of call. To get approved as a drug, it actually worked in humans in robust clinical trials as well.

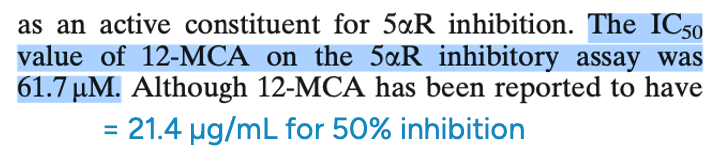

Does rosemary oil work as a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor?

Some people have claimed that rosemary oil can block 5α-reductase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to the more potent DHT which causes androgenetic alopecia (specifically male pattern hair loss). This is promising because it’s how finasteride (another hair loss drug) works.

These claims are based on this paper from Murata and coworkers. But there’s a bunch of problems, because everything rosemary just seems to be problems.

Rosemary extract isn’t rosemary oil

The rosemary extract tested was made by extracting rosemary leaves into aqueous ethanol under reflux for 2 hours, filtering, then evaporating under reduced pressure. This creates an extract with very different components to rosemary essential oil, which is what everyone on social media is recommending – essential oil contains components that evaporate easily, but this procedure extracts mostly components that don’t evaporate easily.

Additionally, the specific compound they think is the active, 12-methoxycarnosic acid, isn’t found in rosemary essential oil (it has a computed boiling point of over 500 °C, so it’s unlikely to be in there to begin with).

Concentrations are too low

But say you decide to extract your own rosemary using their procedure. The problem then becomes concentration – in the in vitro enzyme assay, 2000 times more rosemary extract (by weight) was required to get the same effect as finasteride.

1 mL of 0.25% finasteride is usually used as a scalp treatment per day, so if the rosemary extract was getting into the scalp as well as a really optimised solution of finasteride, you’d need 4.9 grams (0.17 oz) on your scalp. That’s about a teaspoon already – and it needs to be dissolved in something.

In the experiment, 2 milligrams in 100 μL of alcohol for application to rats. This converts to about a cup of liquid for 4.9 grams. Everyone is struggling with getting ¼ teaspoon of sunscreen on their face – good luck applying 200 times that onto your scalp.

They also tested 12-methoxycarnosic acid in the assay, and a lot less was needed – a concentration 230 times more than finasteride gave 50% inhibition (compared to 81.9% inhibition for finasteride – the numbers were reported differently, making this comparison a bit awkward).

But the concentration of 12-methoxycarnosic acid in rosemary is really low: the researchers isolated it in 0.026% yield. To get to 2/3 of the biological effect of finasteride (again, assuming the same penetration through the scalp), you’d use up 2 kilograms of rosemary leaves every day.

Is rosemary oil worth trying?

So is rosemary oil worth trying? In my opinion, no.

The lack of any good clinical trials besides the very questionable 2015 one puts it back at the bottom of the heap in my opinion, as explained above. There isn’t much to support it aside from mechanistic reasoning, which simply doesn’t give it a great chance of working. And the level of mechanistic evidence isn’t high either.

There’s also the fact it’s a natural product. The levels of any potential effective active ingredients in rosemary oil will vary a lot with where and when it’s grown, how it’s harvested and extracted, how it’s stored, and many other factors. For example, there are three main types of rosemary oil, based on what their major components are. It looks like this study used the cineole version (they aren’t clear about this), but even within cineole rosemary oils, there’s a lot of variation.

Essential oils also contain allergens and irritants, and these could actually make hair loss worse. Rosemary oil has camphor, carnosol and cineole, for example, which have been reported to be irritating and allergenic for some people.

We can actually see hints of this in the 2015 study – scalp itching and dandruff increased for the rosemary oil group. Scalp itching increased for minoxidil too, but again, thanks to other clinical trial evidence, we know that any irritation that could lead to hair loss is outweighed by the hair growth mechanisms. But we don’t know this for rosemary oil. (The study doesn’t say how they collected this irritation data though, which is another huge red flag for this study – a study really shouldn’t be missing the methodology for a full page of their results.)

What should you do?

If you do end up trying rosemary oil, make sure it’s diluted to reduce the risk of irritation. Assuming this study used cineole rosemary oil, it was diluted it by about 162 times, which converts to 1 drop of rosemary oil per 8 mL of carrier oil.

It’s also worth considering that hair loss treatments mostly work by helping you keep your current hair and making it thicker, rather than regrowing hair per se. So the longer you try out less proven remedies and delay using more proven treatments, the worse the outcomes will be.

For hair loss, it’s best to talk to your doctor or dermatologist. Sometimes hair loss occurs due to an underlying condition, deficiency or allergy, and hair loss resolves once that’s treated. And depending on the type of hair loss, there are often more proven treatments like minoxidil, which can be used at the same time as trying less proven treatments like rosemary oil. And while sometimes there isn’t a reliable treatment for the hair loss, it’s still a good idea to make sure there isn’t a more serious underlying condition that’s been missed.

Bad information multiplies

The poor quality of this paper highlights a common, but not well-known problem with the scientific literature – peer-reviewed articles cite other peer-reviewed articles, and much of the time they don’t actually look very closely at them.

This rosemary oil paper has been cited 93 times, as of early February 2024. Just as a rough indication of the problem, and how much crap gets through peer review, here are just the first 8 articles citing this paper listed on Google Scholar, along with how many other papers cited them – only one of these even indicates any skepticism about this study.

References

Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, Sahebkar A. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13(1):15-21.

Olsen EA, Weiner MS, Delong ER, Pinnell SR. Topical minoxidil in early male pattern baldness. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 Pt 1):185-192. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70157-0

Olsen EA, Whiting D, Bergfeld W, et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of a novel formulation of 5% minoxidil topical foam versus placebo in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):767-774. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.012

Hasanzadeh H, Nasrollahi SA, Halavati N, Saberi M, Firooz A. Efficacy and safety of 5% minoxidil topical foam in male pattern hair loss treatment and patient satisfaction. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2016;25(3):41-44. doi:10.15570/actaapa.2016.12

Murata K, Noguchi K, Kondo M, et al. Promotion of hair growth by Rosmarinus officinalis leaf extract. Phytother Res. 2013;27(2):212-217. doi:10.1002/ptr.4712

Szumny A, Figiel A, Gutiérrez-Ortíz A, Carbonell-Barrachina ÁA. Composition of rosemary essential oil (Rosmarinus officinalis) as affected by drying method. J Food Eng. 2010;97(2):253-260. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.10.019

Anastassakis K. Androgenetic Alopecia from A to Z. 1st ed. Springer Nature; 2023.

Excellent article. I’m very glad that there are people like you to put studies like this under rigorous scrutiny.

I would like to hear your opinion on castor oil as well. It is commonly recommended on Reddit and other places for use on eyebrows and lashes. Similar to rosemary oil, castor oil seems to be associated with ‘hair growth.’ However of course being a ‘cosmetic’ product rather than a ‘drug,’ it seems there is limited information on the actual effectiveness. The general consensus appears to conclude that castor oil may improve hair growth due to it containing ricinoleic acid and fatty acids, but there being no studies specifically on castor oil it is only speculation.

At the time of writing this comment (3/15/24), searching “castor oil hair” on PubMed returns 13 results, of which less than half seem to be semi-related, and none are clinical trials. Searching “castor oil eyebrow” returns no results. Finally, searching “castor oil eyelash” returns 2 unrelated results.

I very much lack knowledge on this subject, so I would appreciate it if you were to take a look :>